When the Wisconsin Supreme Court on May 13 struck down Gov. Tony Evers’s “Safer at Home” order regarding COVID-19, the Door County Board of Supervisors – and county leaders more broadly – were thrust into an unusual position: the spotlight.

The ruling meant there was no legal mechanism left in place to prevent tourists and seasonal residents from returning to Door County for the summer. And it left unanswered questions about whether county governments had the authority to take action on their own, such as county-wide requirements for wearing face masks and physical distancing.

The County Board this summer discussed but did not enact an ordinance requiring such preventative measures, in meetings characterized by some uncertainty over the county’s legal standing and the process for passing a mandate.

Instead, supervisors focused on public messaging, with a public health advisory in late July and a public information campaign starting in early August. Destination Door County, part of a county-organized recovery task force, worked with member businesses to present consistent messaging to visitors about COVID-19 precautions, centralizing its pandemic-related messaging to tourists on its website and otherwise not broadly changing its marketing campaigns.

The issue has renewed importance this month. With COVID-19 cases surging in the county and with Evers’s statewide mask mandate set to expire Sept. 28, the County Board once again will discuss a county-wide mask mandate at its meeting Tuesday.

The board’s health and human services committee on Monday unanimously supported moving forward with a possible mandate, and both Public Health officer Susan Powers and Dr. James Heise, the Door County Medical Center’s chief medical officer, said they support it.

But county corporation counsel Grant Thomas on Tuesday cautioned members of the board’s administrative committee that it would be wise to wait and see whether Evers extends the statewide mandate—and how such a move could play out in court—before deciding how to proceed on the county level.

Even as some of them now say the county should move forward with a mandate, county leaders have defended their approach this summer, saying they acted thoughtfully and deliberatively and praising the collaboration they saw among the county government, medical officials and leading business groups.

“People who have complained to me have said that there’s been a lack of leadership,” said County Board vice-chair Susan Kohout. “I don’t know that that’s a fair assessment. This was such a new thing, nobody had ever dealt with this.”

Initial county-wide order gives way to legal questions

Immediately following the Supreme Court decision, Powers said, there were a lot of discussions about the county’s options among county leaders—including Powers, Kohout, Thomas, County Board chair David Lienau and county administrator Ken Pabich.

The day after the ruling, May 14, Powers issued a county-wide health order extending the provisions in the state order until May 20. That order was meant to allow the county a transition period after the sudden striking down of the statewide “Safer at Home” order, Powers said.

“The rationale behind issuing that particular health order was simply to extend the guidelines so that we were all on the same page and so that our community could prepare for a relaxation of those,” she said.

“Having said that, was there thought about continuing strict guidelines for longer?” she added. “Of course. It was clear early on that it was all going to be challenged in court.”

Powers on May 19 issued guidelines for reopening the county that outlined recommended preventative measures including wearing face masks, physical distancing, hand washing and limiting travel and large gatherings.

The Supreme Court decision threw the legal landscape surrounding local health authority into a lot of uncertainty, said Andrew T. Phillips (no relation to the author), an attorney who works as the outside general counsel for the Wisconsin Counties Association.

Phillips has faced criticism this week over his work to get the Green Party presidential ticket added to the November election ballot, which would have forced counties to reprint ballots. (The Wisconsin Supreme Court on Monday ruled against the Green Party.) Officials in Milwaukee and Dane counties said their counties should withdraw from the Wisconsin Counties Association, and Dane County Board Chairwoman Analiese Eicher suggested Phillips’s advice to counties regarding COVID-19 was a better fit for Republican-leaning rural counties than Democratic-leaning urban ones. Phillips has a history of working for Republican state legislators and supporting them in legal fights.

“Was there thought about continuing strict guidelines for longer? Of course. It was clear early on that it was all going to be challenged in court.”

Door County Public Health officer Susan Powers

The court ruled that Andrea Palm, the Secretary-designee of the Wisconsin Department of Health and Human Services, exceeded her authority under section 252.02 of the state statutes when she issued the statewide “Safer at Home” order, Phillips said.

That left questions about what actions local authorities, including public health officers and county boards, could legally take under the similarly written section 252.03, he said.

Door County officials also have been watching the progress of lawsuits against local health orders. Those have included a suit against a city-wide “Safer at Home”-style order in Racine that is pending appeal, as well as a federal lawsuit against some state officials and local officials around the state, including Powers, challenging local officials’ ability to issue local health orders. The federal suit was dismissed Aug. 24.

Phillips represented Powers and public health officers in Green and Winnebago counties in the federal suit. Sturgeon Bay resident Thomas Wulf originally was a plaintiff in the suit but withdrew in June.

In order for a local health order to stand up in court, Phillips said, the order must be determined by the court to be “reasonable and necessary,” and it must be grounded in both scientific evidence and the specific circumstances of the municipality or county.

The Wisconsin Counties Association last month released guidance outlining those standards and providing further information about the legal landscape around local health authority after the Supreme Court decision.

The recommended process for mandating COVID-19 preventative measures in a county is twofold, Phillips said. First, the county’s public health officer would issue an order requiring those measures, and then the county board would pass an ordinance making that order enforceable, based on section 252.25 of the Wisconsin statutes.

Deliberation and confusion in County Board discussions

The sudden and significant influx of visitors and seasonal residents as early as May seemed to catch the county by surprise.

“All of a sudden there were a lot of people,” said Kohout, the board vice-chair. “Even in May, earlier than people expected. … There was panic then.”

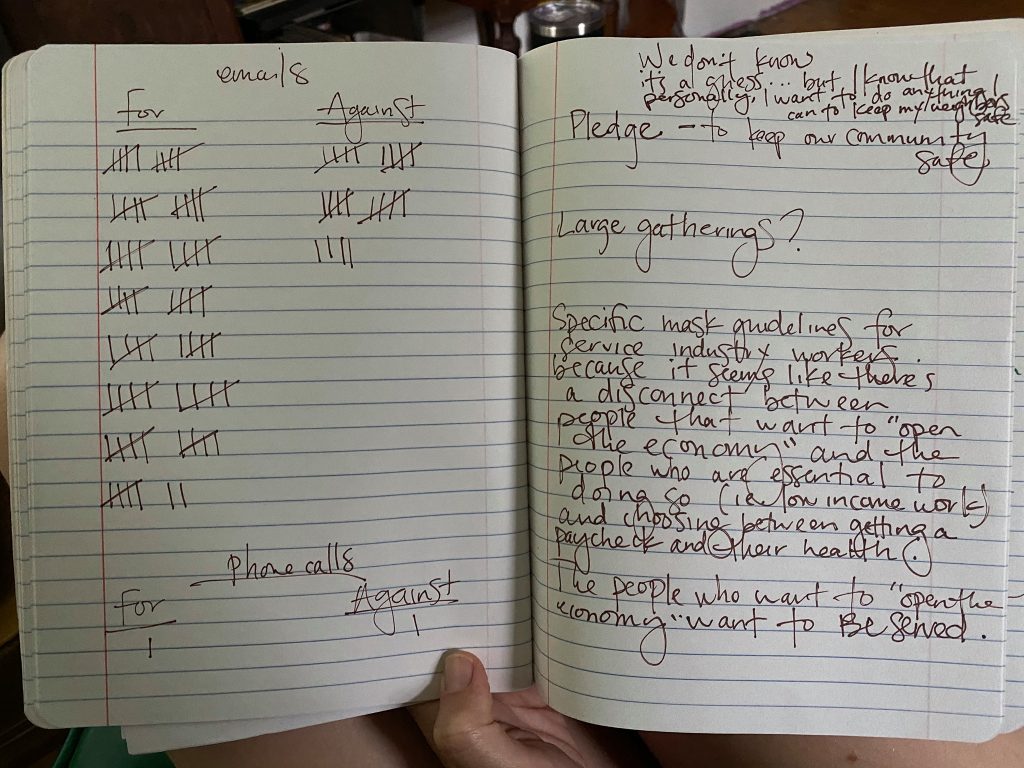

When the County Board in July discussed the possibility of a county-wide ordinance requiring preventative measures, however, county supervisors cited legal concerns—including the Racine and federal lawsuits—though some supervisors said the calls and emails they got from the public were overwhelmingly in favor of a mandate. Officials from the Door County Medical Center, Destination Door County and the Door County Economic Development Corporation also told supervisors they would support one.

The legal concerns were driven more by thinking about what action would be the most effective than by the potential costs of litigation, Pabich said in July.

“If you know something’s (invalid), if you know that up front, you’re just not going to pursue it,” Pabich said.

While legal concerns are legitimate, they should not stop the county from acting to protect residents, said Megan Lundahl, the chair of the County Board’s health and human services committee.

“I feel that it’s our responsibility to do what is in the best interest of the whole, and to vote with our constituency,” Lundahl said. “If that is in a gray area of the law, that does not change our responsibility. So really it doesn’t weigh in much for me, or at all.”

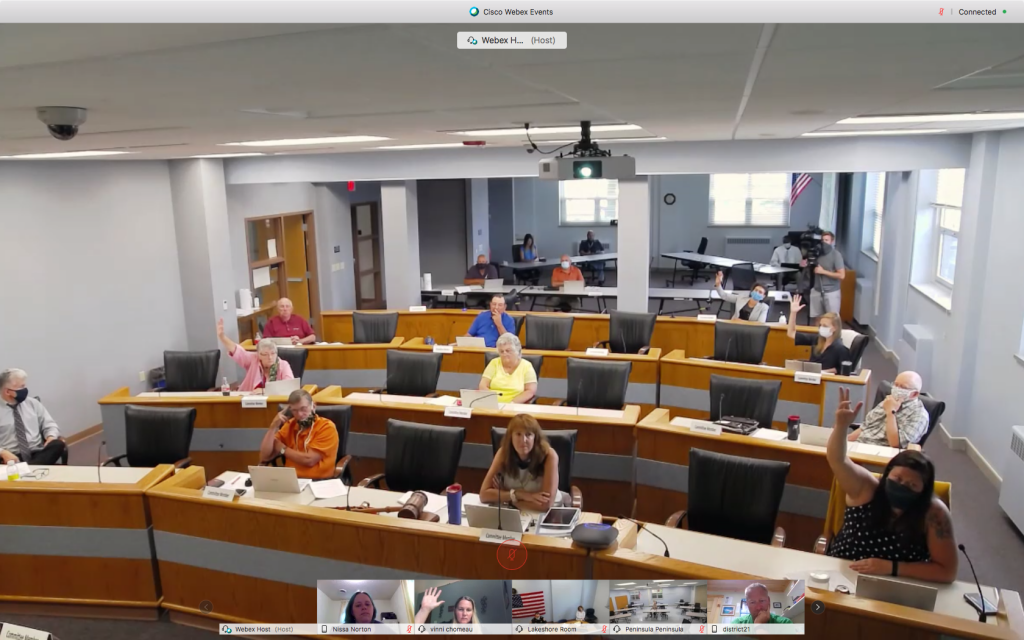

Procedurally, Lundahl said, the board could have handled some things better over the summer. She pointed to a confusing show-of-hands vote in a July meeting on whether county staff should draft an ordinance; some supervisors had phoned into the meeting and others were not in the room at the time of the vote.

“That could have very easily been taken care of in a different way,” Lundahl said. “There’s a learning curve to all of this. We’re laypeople … we’re not professional politicians by any sense of the word.”

Kohout pointed out that the mask mandate issue also arose on the heels of an election that resulted in five new supervisors on the 21-member county board. The pandemic limited opportunities that supervisors usually would have to meet each other and gel as a board, Kohout said, including things as simple as having coffee and donuts together.

“That’s not an excuse,” Kohout said. “… But if we were not off like a shot, that’s part of it.”

Lundahl said her perception was that some supervisors were waiting for Evers to take action statewide.

“A lot of members—about half, it seemed—really didn’t feel like it was the county’s place, that it wasn’t within our jurisdiction,” Lundahl said. “The other half of us thought it was, and that it was something we needed to do ASAP.”

Kohout said she’s not sure whether she wishes the board had acted sooner.

“I supposed I’d have liked it if we’d have all been of the same mind, but that’s not realistic,” she said. “That’s not how this thing works.”

In spite of the disagreements they have, Kohout said, she believes supervisors approach their role sincerely wanting to do the right thing, and not acting out of ideology.

In messaging, a focus on consistency and—later—preventative measures

After seeing survey data in late spring that showed a vast majority of potential visitors were willing to wear face masks, Destination Door County did not broadly change its marketing campaigns for the summer, director of communications and public relations Jon Jarosh said.

The survey, sent by Destination Door County on May 14 to its email marketing list, showed that among 10,432 respondents, 87 percent said they would be willing to wear a face mask while visiting the county this year.

“We were curious because we didn’t know how much we needed to focus on the safety aspect,” Jarosh said.

The survey results confirmed county marketers’ initial ideas for how to approach the summer, he added. As a result, on advertising channels including streaming video services such as Hulu, streaming audio services such as Pandora and Spotify, and electronic billboards, Destination Door County somewhat revised its messages, but most were similar to what the group had originally planned, Jarosh said.

“Most of our revised messaging portrayed wide open spaces to explore, but didn’t directly address wearing masks,” he said in an email.

County marketers tried to use those channels to funnel people to DoorCounty.com, Jarosh said, where a travel updates page providing information about COVID-19 and precautions has been among the most popular pages on the site this year.

“If we’re asking visitors to wear a mask in communications they’re seeing from us before they get here, we certainly want to have that same message while they’re here.”

Jon Jarosh, Destination Door County’s director of communications and public relations

That page has included a video released in July featuring Jarosh, Heise, Powers and Pabich and encouraging visitors to wear face masks, wash their hands and maintain physical distancing.

That video, and another in May from shortly before the Supreme Court decision, have featured more prominently in Destination Door County’s social media posts and email newsletters, where county marketers have more directly addressed COVID-19 precautions, Jarosh said.

Much of Destination Door County’s work related to COVID-19 has been focused on working with its members and other businesses to develop consistent messaging, Jarosh said.

The organization, working with the county recovery task force, started a “Commitment to Cleanliness and Safety” initiative in May, providing businesses with a flyer, a logo and other materials if they pledged to follow health guidelines and asked their customers to do the same.

The initiative was part of an effort to have consistent messaging to tourists across the board, Jarosh said.

“If we’re asking visitors to wear a mask in communications they’re seeing from us before they get here, we certainly want to have that same message while they’re here in-destination,” he said.

Separately, the county in early August started a public information campaign about COVID-19 preventative measures that targets both residents and tourists, in part in response to questions by some supervisors at County Board meetings about the county’s messaging.

The campaign includes electronic billboards and print and radio advertisements and is paid for by the county, Pabich said, though the messaging was developed through the recovery task force. The campaign is scheduled to run through the end of October, Pabich said.

County Board to discuss mask mandate Tuesday

Moving forward, Kohout said she’s not sure if there are enough votes on the County Board to pass a county-wide mask mandate.

But at the health and human services committee meeting Monday, she pointed out that supervisors know more now than they did the last time they discussed a mandate: the federal lawsuit has been dismissed, and while the Racine lawsuit still is pending, other local mask mandates, such as the one in Dane County, are still standing.

Kohout said her thinking has shifted on the issue. Initially, she said, she was concerned about whether a county-wide mandate would be enforceable. (The Door County Sheriff’s Office has told supervisors it does not have the personnel to enforce a mandate.)

Now, though, Kohout said she thinks the County Board needs to take a stand.

“I was tentative early on about it, but at this point, I’m happy to vote for it, because I think it’s the right thing,” she said. “And let the chips fall where they may.”

Lundahl said the board has a duty to listen to residents.

“When we have 70 to 80 percent of our constituents practically begging us to do something, anything within our power, we should be reacting to that as a government body,” Lundahl said.

Looking back, Kohout said she thinks the county did the best job it could.

“Was our response perfect?” Kohout said. “No, I’m sure it wasn’t. But I don’t apologize for it. I really truly feel people have worked hard on this and spent a lot of time.”