Exacerbating recent funding issues for Door County Habitat for Humanity, flooding in late June at its headquarters and ReStore location in Sturgeon Bay resulted in roughly $45,000 in damages.

The flooding at the store in June was at least partly due to outdated city infrastructure, according to Sturgeon Bay City Council Alderperson Kirsten Reeths. Reeths represents District 7 in the city, the area where the ReStore is located.

The ReStore is a home improvement resale store operated by Habitat employees and volunteers. Proceeds from the sale of donated goods at the store go toward helping people achieve decent and affordable home ownership, according to the organization’s website.

According to its 2022 Form 990 filed with the IRS, Habitat had about $694,000 in total revenue in its fiscal year 2022, down from about $998,000 in fiscal year 2021.

Thanks to a cooperative effort led by the Door County Housing Partnership, Habitat has the opportunity to put volunteers to work on a new home build in 2024. Grant funding from a state grant directed by United Way of Door County allowed the Housing Partnership to purchase 10 lots in Sister Bay with plans to build homes on them, while Habitat will provide much of the labor to build the first home in that project.

An April 11 press release from Habitat previously stated that it would not be undertaking a build of its own this year. The organization made that decision because of financial constraints and because it was not able to secure a partner family, according to Allen.

The organization built two homes and undertook a home renovation in 2023, Habitat board of directors president Carrie Becker said, and that “aggressive” approach to building contributed to the financial constraints in 2024.

Water rising

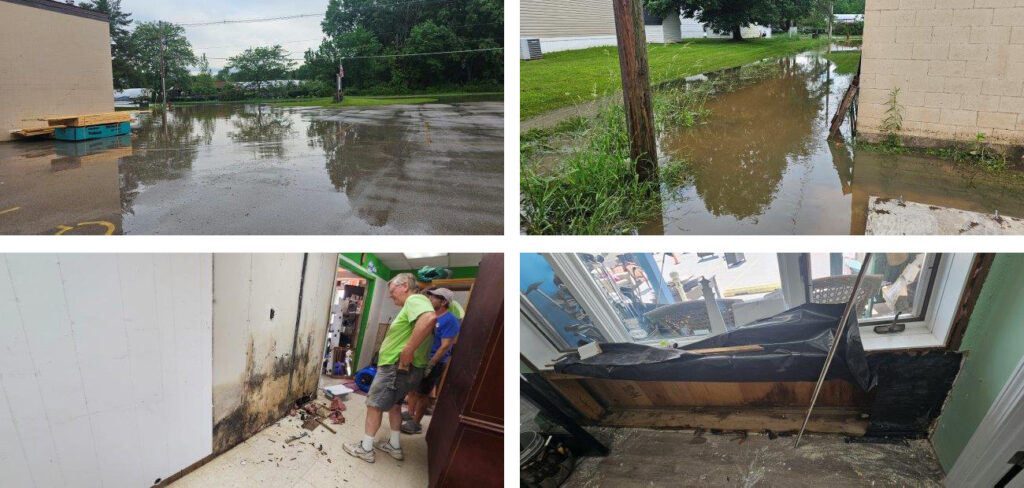

June 25 brought heavy rains, thunderstorms, power outages and localized flooding to Door County. Habitat’s headquarters and ReStore facility, located at 410 N. 14th Ave. in Sturgeon Bay, experienced flooding.

An estimated 6 to 8 inches of water was standing in and around the building when employees arrived at work that morning, according to ReStore manager Heather Thyrion, who has been with the organization for 14 years.

“It was all under water,” Thyrion said. “When the waters eventually receded we could see how bad it was.”

All of the flooring and the bottom 3 feet of the building’s walls needed to be torn out and replaced, and countless dumpster loads of ruined furniture and other items had to be thrown out, Thyrion said. The store cannot re-sell water-damaged items, especially when the water is brown and full of questionable bacteria, she added.

Storm drains were overflowing, according to Thyrion, and the natural runoff area next to the building on the south and west sides was overfilled.

“The water had nowhere to go,” she said.

The ReStore closed for two weeks so staff and volunteers could clean and replace everything. The Habitat team did all the repairs themselves, with some additional community help, Thyrion said. People donated beverages for the crew; Walmart donated gift cards; and CNC Restoration in Green Bay delivered 42 fans to help dry out the building.

All told, the flood caused about $45,000 in damages, and none of that money was covered by the organization’s insurance, according to Allen. Habitat’s flood insurance only covers water that comes through the roof, she said.

The organization has raised about $30,000 to cover the costs of the $45,000 lost to flood damage, Allen said.

Most of it was from private donors who earmarked funds for flood damage, according to Becker.

Some of those funds went toward tearing out the fiberglass insulation in the bottom half of the building’s walls and replacing it with foam board, Becker said, ensuring water will drain rather than be absorbed by the insulation.

Some of the money is being spent on remedying the ReStore property by diverting water from the foundation, Becker said. But if there is another “perfect storm” like the one in June, she said, there is not much that can be done to stop more flooding.

About $3,000 of the money needed for these efforts was raised at one fairly impromptu “grand re-opening” fundraiser in the ReStore parking lot in mid-July, according to Thyrion. Volunteers and staff members’ friends and family gathered, publicized the event, got a band together and brought in a food truck to celebrate what was the end of a lot of exhausting and frustrating hard work for the Habitat team, she said.

Infrastructure needs

Flooding like this has happened before and it will continue happening, Reeths said.

District 7 is one of seven districts in the City of Sturgeon Bay and is bordered by 18th Avenue and 7th Avenue to the east and west, and Georgia Street and MIchigan Street to the north and south. The ReStore sits right in the middle of the district.

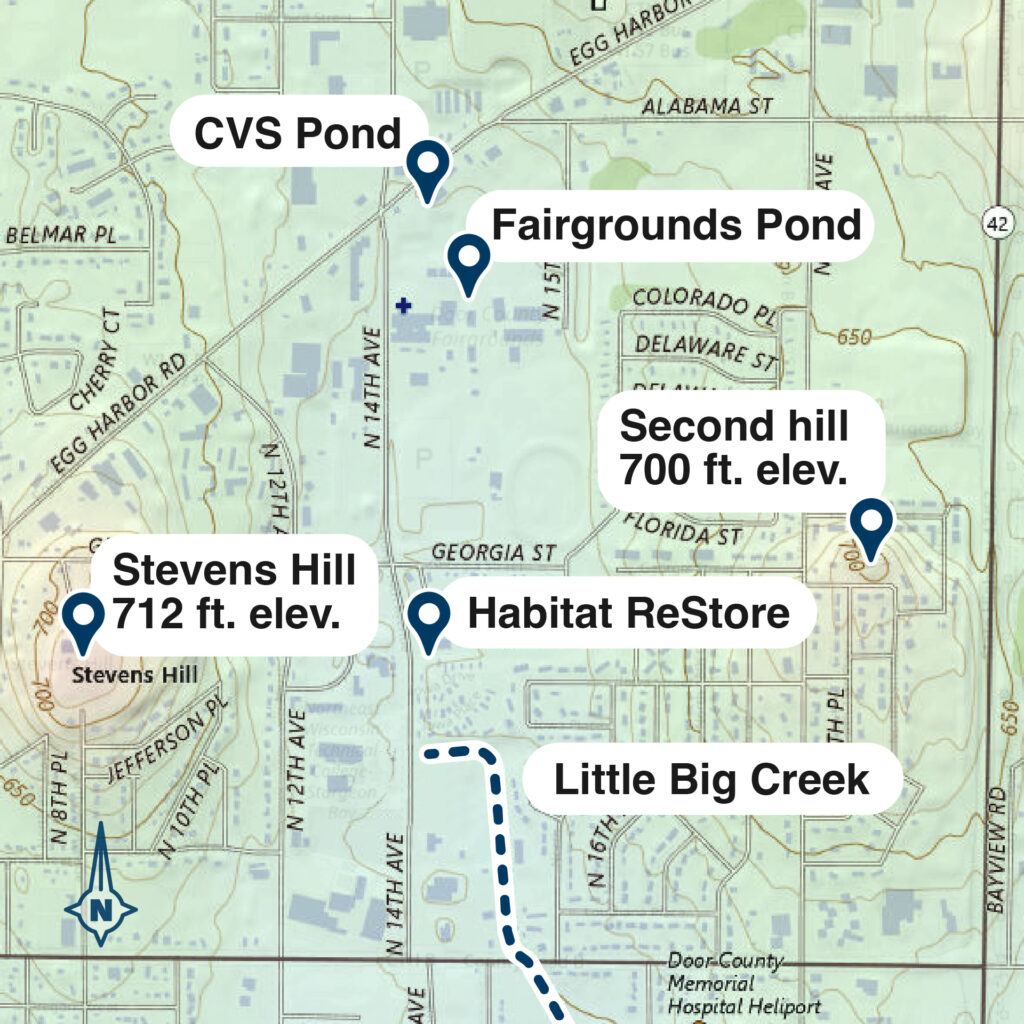

The ReStore is also essentially in a valley, between high points of the city, said Mike Barker, municipal services director for the City of Sturgeon Bay Department of Public Works.

There is Stevens Hill to the west of the ReStore and, Barker said, other hills to the northeast and east of the store.

“Georgia (Street) runs down from one and up the other (hill), but yes, ReStore is in a low point,” Barker said.

There is new development in the area, and more development has been proposed, potentially adding to flooding concerns, according to Reeths.

“There are consequences when you just keep building,” Reeths said.

A proposed apartment project is about a half mile away from the ReStore, but any development could potentially add to flooding issues in the area, Barker said. He also referenced a hotel project planned for the intersection of 12th Avenue and Egg Harbor Road.

“Any time you add more impervious surfaces, you’ll have drainage issues to figure out,” Barker said. “Every time there is building, there are talks about needing to move water.”

Retention ponds and swales, or low places in the ground, are some ways water drainage can be managed, he added.

Flooding in District 7 has been an issue for a long time, according to both Barker and Reeths. The city has ideas about how to address it, Barker said.

“We have so many things high on the priority list for public works,” Barker said. “I would say this is in the top five. It’s a rather large project.”

Part of the project would include addressing a small creek, too small to have an official name. The creek, which Reeths referred to as “Little Big Creek,” runs behind the ReStore and through dozens of properties on its way to Big Creek, ultimately ending up in the bay of Sturgeon Bay.

The creek is designated a navigable waterway by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, according to Barker, and the city is limited in what it can do without permission from private property owners. The city removes heavy overgrowth and does some mowing in the creek area, he added.

Parts of the creek have been filled in by private property owners, and it does not flow steadily enough to provide the natural drainage it used to, Reeths said. Between that and heavier rainfalls, the water has nowhere to go but “back out and back up,” she said.

At a city budget meeting on Sept. 30, Reeths said, she plans to make a recommendation for the city to build another retention pond in the area on city-owned property.

There are two retention ponds already, one behind CVS Pharmacy and one at the county fairgrounds. Reeths also plans to recommend the city hire Cedar Corporation, an engineering and architecture firm in Green Bay, to look over the area and find out exactly what else needs to be done to clear Little Big Creek and mitigate future flooding.

It might take sending letters to property owners, easements, and most of all, money, but “the need is now,” Reeths said.

The need could be alleviated with financial help from the federal government to update and improve infrastructure, she said, but not until 2030. That is when the next census comes out, and in order to receive federal aid for infrastructure upgrades, the city needs to have an official population of more than 10,000 people.

Right now, the city’s population is 9,926.

Reeths said she guesses there are already more than 10,000 people in Sturgeon Bay, but that is not official until the next census. The official number also does not take into account visitors and seasonal residents, she said.

“People don’t want to talk about this—what the infrastructure can handle—because it costs money,” she said. “It costs lots of money.”

Financial effects of repeated flooding can be potentially catastrophic for the city and for homeowners, she added.

Opportunity

Putting catastrophe aside, a groundbreaking ceremony at 2423 Ava Hope Trail in Sister Bay on July 30 celebrated the combined efforts of Habitat, the Housing Partnership and several other organizations helping with affordable housing issues.

A three-bedroom, two-bathroom dwelling will be built on the site, providing a home for a local child care worker, Allie Hernandez, her husband and two small children. The house and nine more like it will be built on land purchased from the Village of Sister Bay by the Housing Partnership with money it received as part of a $3.5 million state grant awarded to various Door County child care and housing groups through United Way of Door County.

The village sold the parcels at $10,000 apiece and the Housing Partnership will purchase all 10 of them with the money it received from United Way. United Way received the $3.5 million Workforce Innovation Grant in December 2021 from the state Department of Workforce Development and the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation.

The focus of the grant is for child care, United Way Executive Director Amy Kohnle said, and investing in infrastructure to support it, including more child care centers and teacher education. (Disclosure: Kohnle is also a donor to Knock.)

Because United Way knew that a lack of affordable housing was a huge barrier to finding child care workers, Kohnle said, the organization wrote housing into the grant as well.

Habitat is “thrilled” to partner with the Housing Partnership on this build and others, said Allen, the Habitat executive director, and it will coordinate volunteers for construction.

This one is different from partnerships in the past though, according to Becker, the Habitat board president. Habitat volunteers are not building a home for Habitat; rather, the volunteers are forming the construction crew that will build the Housing Partnership’s home, and providing site management.

The Housing Partnership is providing the funding and the family. In an interesting turn of events, the Hernandez family originally applied to Habitat and didn’t qualify because it qualified for a loan instead, Becker said.

“Lori (Allen) has the biggest heart,” she said. “She hated telling them no.”

Allen got in touch with Mariah Goode, the Door County Land Use Services director and a member of the Housing Partnership’s board. That set the family on the right path and helped them connect with the Housing Partnership, Becker said.

The partnership with the Housing Partnership continues Habitat’s mission, she added, allowing Habitat to be a part of providing a home for a family.

This home and nine others will follow a community land trust model, which allows for homes to stay affordable into the future. According to the model, the Housing Partnership will lease the land to the owner, but the homeowner will own the house.

In the lease, there are restrictions on how much the homeowner can sell it for and who can buy it. The homeowner can gain equity, but the house remains affordable for the next workforce buyer.

A need for funding, and applicants

Habitat is working to secure grants, Allen said, but it still needs corporate and individual donors to be able to continue new home build partnerships like the one with the Housing Partnership.

Habitat received a large donation from a private individual’s estate two years ago, Becker said, and a previous iteration of its board wanted to concentrate on more building in 2023. Two new home builds and a home renovation contributed to lack of funding for a new build this year, she added.

Costs went up as well, she added. The cost of building a house went from about $150,000 to between $200,000 and $250,000 since the Covid pandemic.

“Our homes have to be affordable based on the family’s income,” Becker said. “The difference between the house cost and what a family can afford is getting bigger and bigger. This year is a regroup. We want to have funds for the full cost of our 50th house next year, and funds for savings.”

Until then, Habitat continues to provide other services and programs for residents in need, Allen said.

Through the Ramp Up Door County program, Habitat installs and leases temporary mobility ramps for residents who need physical and financial assistance to stay in their homes. Habitat also helps with home repairs for qualified residents and provides assistance with deconstructing homes for usable materials it can re-sell in the ReStore, Allen said.

Besides money, the organization always welcomes volunteers. Volunteers do not have to have building experience, Allen said, and she encourages organizations or businesses to send a crew to build.

“And there’s a need,” Allen said. “Every house that we can build is going to help someone. It truly comes down to funding. More funds and more volunteers.”

There’s also a need for more applicants, Becker said. Currently there are no applicants in northern Door County for a home, she said. The lots for the homes to be built with the Housing Partnership are all in Sister Bay.

Requirements for Habitat for Humanity applicants are based on numbers from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Applicants must make less than 80 percent of the median income for the area, have the ability to pay, be working, provide 250 hours of sweat equity toward their build, live in Door County for 12 months, and undergo credit and background checks.