Real heroes don’t wear capes. They wear glasses, sweet smiles, and sometimes, bright orange tube socks.

Ben Anderson still has the socks he wore during high school cross country meets and baseball games. They were a visual reminder of the message another young man, named Bo Johnson, was spreading through Door County and beyond in 2012, while battling a rare form of cancer: Pay it forward and help each other.

Today Ben is 29 years old and facing some serious medical issues of his own. In 2012, he was about five years older than Bo when Bo died of the rare extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia he had been diagnosed with a year earlier at the age of 12. Both of them attended Gibraltar schools and played Little League baseball, growing up in the same close-knit community. Ben said he still gets goosebumps when he thinks about the speech Bo made in the Door Community Auditorium the year he passed away.

“He spoke about paying it forward and being part of the community, helping one another,” Ben said.

Ben uses that phrase a lot, “paying it forward.” He also mentioned community and helping people at least a dozen times in an hour-long Zoom interview.

Ben was a high school junior when Bo died, and he remembered how the whole community rallied behind Bo. He said he was inspired by Bo’s message, his fight, and his bravery.

Many people were inspired by Bo Johnson, as happens when someone so young dies of an incurable illness. People talk about their bravery, their strength. Maybe they say prayers, maybe they are a little nicer to everyone around them. If they are really moved, maybe they donate money to a cause that supports other people with similar illnesses.

Some of them might sign up to donate blood, bone marrow or stem cells for those diagnosed with similar conditions. Fewer still are a match and get the opportunity to do so.

Virtually none of them undergo a surgical procedure to have part of a vital internal organ removed for transplant to save someone else’s life.

None of them are Ben.

Live liver donation

A live liver donation is when a healthy person has one third of their liver removed and transplanted into a person with an unhealthy or non-functioning liver. Because the liver is an organ that regenerates itself, the donor’s liver will regrow to normal size eventually and the recipient will have a functioning liver.

There are few live liver transplant programs in the country, but Wisconsin is home to one of them, at Froedtert Hospital in Milwaukee.

Ben saw a social media post in August 2019 about a young child in need of a donation. “It got me thinking. It stood out to me,” Ben said. “Paying it forward, helping one another. I’m healthy, I’m in a position where I could help someone else.”

He began looking into live liver donations, and while he was unable to help the particular child in the social media post, he went through testing to be placed on a potential donor list.

In October 2019, he got blood work done for the program. In November, Froedtert identified a few potential matches for Ben’s liver. One of them, a three-year-old from Iron Mountain, Mich., was the best candidate.

Ben thought, “Okay, we’re gonna go for this.”

On Dec. 5, 2019, Ben underwent an almost eight-hour surgery at Froedtert. One third of his liver was removed and placed into that three-year-old child from Michigan. Because it is an anonymous donor program, he did not know anything else about the recipient.

He says that little detail did not matter to him. What mattered was giving a child another shot at life, with Bo in mind.

Stem cell donation

The live liver donation was not Ben’s first experience with medical donation. When he turned 18, he signed up for the NMDP registry. In 2024, NMDP changed its name from Be the Match, but its mission remains the same: saving lives through cell therapy. The organization started in 1987 as the National Marrow Donor Program.

NMDP maintains a registry of potential donors. If someone wants to sign up, they fill out a brief medical questionnaire, receive a cheek swab kit in the mail and return their sample back to NMDP. Their details are then kept on file until the potential donor is 61 years old or opts out of the list, or until a match is found.

Bo’s efforts brought the registry to the northern Door County community’s attention when he was ill and encouraged others to sign up. He not only wanted to see if there might be a match for him, but to add to the list of potential donors, according to Ben. Bo knew there was a long list of patients suffering from a blood disease who could benefit from cell therapy like bone marrow and stem cell transplants.

In 2014, at the age of 18, Ben joined the registry. In 2015 he was identified as a match for a patient in Canada. He underwent a procedure that included receiving injections to stimulate bone marrow growth, followed by what is sometimes several hours of getting stem cells harvested from one’s blood via IV.

He was happy he was a match at all, Ben said.

But that was not the end of the story.

The donation was anonymous, but in anonymous donations, donors and recipients can find out about one another if both parties agree. Ben had agreed the recipients could contact him if they wanted to in both medical donations he underwent.

The daughter of the man whose life was saved by Ben’s stem cells reached out to him shortly after the transplant. She gave him her father’s contact information, and told him that he is healthy and enjoying life with his children and grandchildren.

Ben has communicated with his stem cell recipient several times since then. The man is French-Canadian and speaks French, so they stay in touch with Google Translate, Ben said.

Every year 18,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with serious illnesses for which a bone marrow or blood cell transplant is their best treatment option, according to the federal Health Resources and Service Administration. About 70 percent of those people do not have a match who is related to them.

Because blood cell therapies like stem cell transplants hinge on more complicated matches, rather than blood type, finding a match is more difficult than in a standard blood donation. There are only three options for blood types, while the markers needing to be matched for stem cell transplants have millions of possible combinations

Before and after his own experience with stem cell donation, Ben organized “swab drives” at his high school and at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, where he attended college.

He also donated blood regularly in high school and college and helped run blood drives.

It’s a mom thing

In fact, every major choice Ben has made in his young adult and adult life seems to exemplify that phrase Bo talked about in his speech—paying it forward. From Ben’s education to work history, he has always been helping people.

He graduated from UW-Whitewater with an early childhood education degree and is pursuing an advanced degree in infant and adolescent development with an emphasis in mental health counseling at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. He has worked as a substitute teacher, volunteered at a crisis hotline, and worked for the Minneapolis Crisis Nursery, a respite care facility for children under six whose families are experiencing homelessness, domestic abuse and other critical issues.

He currently works for a food bank in the Twin Cities, where he helps coordinate food donations from retail businesses to other organizations’ food pantry shelves.

Tammy Anderson is Ben’s mom. She works two jobs, one at Piggly Wiggly in Sister Bay, and another at Sister Bay Bowl, where she has been for 38 years. She said Ben and his brother, Chris, grew up in the service industry and Ben did not realize serving people was her paying job until he was seven or eight.

She described Ben as a soft-hearted kid, who had developmental challenges that were treated with occupational and physical therapy when he was a preschooler. Tammy said the staff at Gibraltar was instrumental in helping Ben. He went on to a successful school career in Gibraltar and was prom king, Sadie Hawkins dance king and on Homecoming Court. She said he played lots of different sports, even though he wasn’t very good at them, according to Tammy, but all the other kids wanted him on the team because he was a morale booster.

“He picked everybody up,” she said.

Nicole Mottl agreed and said Ben is a rare person in a generation of young adults used to social media connection often filling in for “real” connection. She met him when they were both in the early childhood education program at UW-Whitewater, and they have been good friends since.

Nicole described a two-month-long study abroad trip to Ecuador they took together during college. She said that Ben still keeps in touch with his host mom. She said one of the things she really likes about Ben is he genuinely wants to get to know people, and go deeper than “surface level” friendships.

When he decided to donate part of his liver, Nicole said she was not surprised at all. “Giving up part of his body to save someone else…it’s a Ben Anderson move,” she said.

Tammy said she and Ben’s dad, Gary, were a little scared when Ben told them about his decision to make a live liver donation in 2019. “But then we looked at each other and said, it’s Ben,” she said.

“Ben will push through this,” they agreed.

The family spent a long time talking with transplant care team members at Froedtert before the surgery, Tammy said, which went a long way toward helping his parents feel comfortable about the process.

“It is hard to see your child hooked up to machines, in pain,” she said, “but knowing it was not related to a life-threatening illness, knowing it was for something amazing…” Her voice trailed off.

Tammy has put herself many times in the place of Annika Johnson, Bo’s mom, and the mother of the little boy who received Ben’s liver. She knows how blessed she is not to have the daily pain of wondering if her child will live or die. She said it is all intertwined, what each mother has gone through.

“Annika’s (son) died,” she said. “Ben saved Kayla’s.”

Kayla Perron is Micah Perron’s mom. Today Micah is a healthy eight-year-old boy who loves dinosaurs, taekwondo and bouncing off the walls with energy, like any other kid, according to his mom.

Ben and Micah met in person a few weeks after one third of Ben’s liver was removed and placed into the little boy’s body. Micah’s family reached out via the transplant team to thank Ben and invited him to the hospital where Micah was recovering. The two of them met in what was an emotional moment for everyone in the hospital room, Kayla said.

For the last five years, Ben and Micah have called, texted and FaceTimed with each other a couple times a month. They call each other Best Buddy Ben and Little Buddy Micah. They don’t talk about the liver anymore, Ben said. Instead, they talk about LEGO and dinosaurs and taekwondo.

Micah was born with a life-threatening condition in which his liver did not create a protein needed for metabolization. When he was six weeks old, he was very jaundiced, Kayla said, which led to a diagnosis and three very long years of medication, donor lists and her little boy being sick constantly.

Ben said meeting Micah in the hospital was like the end of a Hallmark movie, where all the main characters come together and everyone is happy. As he learned more about the family, Ben said, he realized how much they had really needed “a miracle.” The family had been through unimaginable loss, he said. Micah’s older sibling died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome before Micah was born.

The Perrons were curious why such a young person like Ben would do something like a live liver transplant, he said, and he told them about Bo. Micah himself is still a bit young for that conversation, Ben said, but he thinks Bo’s message about paying it forward and helping one another lives in Micah regardless.

“He knows it from what someone did for him,” Ben said. “I’ve seen it firsthand. He’s helping other kids at taekwondo—he’s a leader already.”

Kayla said when she first met Tammy, she remembers thanking her for raising such a good person. “I’ve never met a nicer guy, to be honest,” she said. “I can never put into words how thankful we are.”

Annika Johnson was reached for comment, but temporary illness prevented her from more participation in this story. Perhaps the text with which she responded to a request for comment sums up her feelings enough, however:

“I love Ben.”

You can’t make this stuff up

Recovery from the live liver transplant took Ben a little more than a year.

“I’m not going to sugarcoat it, it was the most pain I’ve ever been in, coming out of that surgery,” Ben said. But he added that he has no regrets and would do it again.

He remembered laying in the hospital bed, being prepped for surgery and knowing it was where he needed to be. He felt everything aligned to make the donations happen and said he is fortunate to have done it when he was able to do it.

As of last spring, Ben cannot even donate blood anymore. In April 2024, three months after starting his new job with the food bank, right in the middle of his graduate school semester, he was diagnosed with hydrocephalus, a condition where fluid builds up in the skull and causes brain injury. His condition is not related to his medical donations, Ben said.

Shortly after diagnosis, he underwent brain surgery, in which complications led to a traumatic brain injury. Ben now finds himself an involuntary patient with a lifelong health condition.

He has weekly appointments with an occupational therapist and a speech therapist and sees his neurologist regularly. His eyesight, cognition and memory have been impacted. He has retained his job with the food bank, where he receives medical benefits, but he is not able to be in school again until he heals more, he said.

To make matters even worse, while he was recuperating from brain surgery, Ben was involved in a car accident in which he sustained a concussion which led to setbacks in his recovery. He is on week seven or eight of a constant headache, he said.

“I’m not a writer, so maybe you can make this stuff up,” he joked wryly.

While his hydrocephalus and traumatic brain injury are lifelong conditions, Ben said his doctors think he can make enough progress with therapy to mitigate any visionary and cognitive impairment. He said it is a long and uncertain road, but he is taking it day by day.

Ben expressed gratitude for his care team, his family, and his community. He said he is homesick for Door County but knows Minneapolis is where his doctors are and where he needs to be right now. The Door County community has rallied around him, though, much like it did for Bo so many years ago.

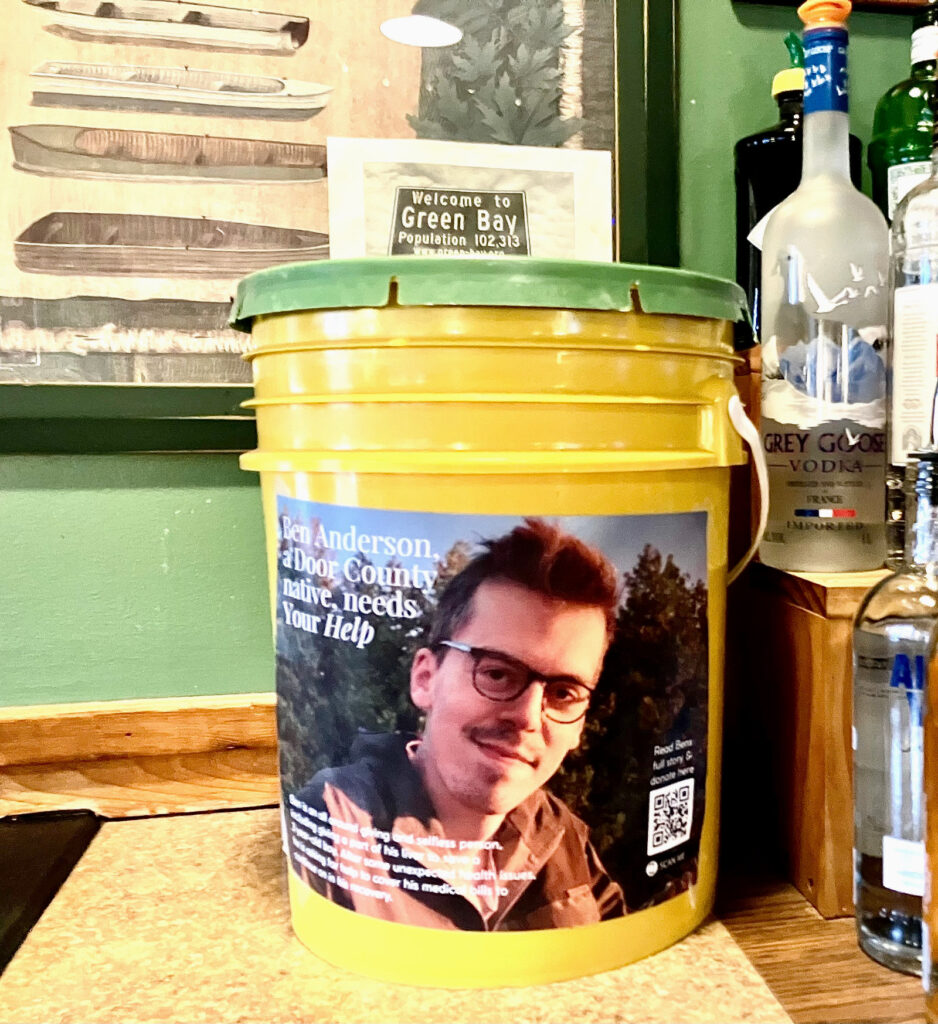

His friend Nicole started a GoFundMe campaign for living and medical expenses while he recovers. She started it with his consent, she said, but he took some convincing. (Disclosure: Knock executive director and editor-in-chief Andrew Phillips donated to the GoFundMe campaign in April.)

“He has a hard time asking for help,” Nicole said. “It was a big deal to open up about his health issues.”

Ben agreed it is hard to accept help, when he is the one used to helping. The outpouring of support, both emotional and financial—Ben could not work for months and, despite insurance, has substantial medical bills—is staggering, he said, and he does not know where he would be without it.

He said he understands better what his medical donation recipients went through now.

“You’re helpless,” Ben said. “When you lose your health it shines a light on how vulnerable you are. How every little thing matters.”

Ben’s GoFundMe campaign raised almost $25,000 in its first 24 hours. He and Nicole have since upped the goal, as his health issues continue, and the donations keep coming with $49,362 of the $50,000 goal currently met, Nicole said. These results speak to what kind of person Ben is and how loved he is, she added.

Sister Bay Bowl, where his mom works, hosts the Barney Fun Run and Walk every year to raise money for different causes. This year’s run was for Ben. There are also plans in the works for a benefit concert later this year, Nicole said.

“Between giving everything his entire life and the connections he’s kept up with,” she said, “he’s got a pretty big village behind him.”

Ben’s mom is confident he will make it through this hurdle just fine, but Tammy also admitted to being “petrified” when he was first diagnosed. She said she can empathize with what the other moms faced when Bo and Micah were sick.

“As a mom, you wish you could just take it all away,” she said.

While focused on his own recovery, Ben said he wants to be clear about the choices he has made to help other people.

“I never once doubted those decisions were for someone else,” he said. “It wasn’t for me, it wasn’t for my family, it wasn’t even for Bo. I didn’t do it for fame, I didn’t do it to feel better about myself. I did it for someone else, to give them a chance to live a life that I’ve been given.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the year when Bo Johnson died. He in fact died in 2012, not in 2011. The story has been corrected.