Second and third rounds of private well testing in Door County show local groundwater continues to be generally safe for the residents and visitors who depend on it for drinking water.

“We do have areas that we want to look at a little bit further, however these are limited in number,” according to Sheryl Stephenson, a GZA GeoEnvironmental project hydrogeologist. “It’s not like there’s hotspots all over the peninsula that we’re trying to chase down.”

Stephenson presented the latest results of the four-year Door County Groundwater Sampling Protocol and Preliminary Screening project in a report to the County Board of Supervisors on Jan. 28. GZA was hired by the county in October 2023 and has conducted three rounds of sampling since then.

Stephenson reported on results of the initial round of testing at a January 2024 County Board meeting. The program has since conducted two more rounds of testing, one in spring 2024 and one in fall 2024.

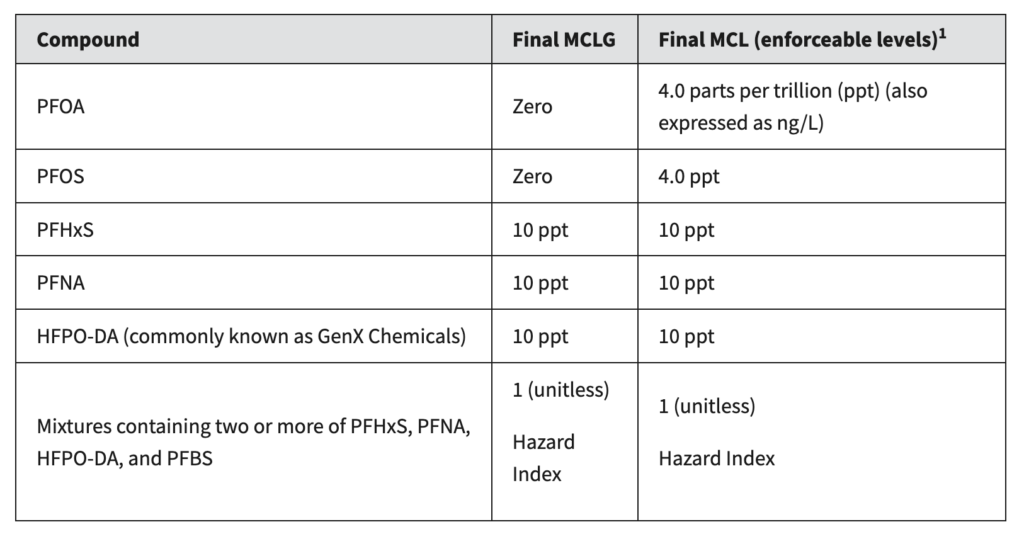

Additionally, the Environmental Protection Agency finalized drinking water standards related to per- and polyfluroalkyl substances, or PFAS, since the first round of testing and reporting. On April 10, 2024, the agency established legally enforceable levels, called maximum contaminant levels, for six types of PFAS.

GZA relies on the EPA’s latest standards, Stephenson said, while the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources relies on the state Department of Health Services’ drinking water advisories issued in 2020.

Wisconsin has not established updated groundwater quality enforcement standards for PFAS, but last May, the DNR requested that the Department of Health Services do so using the more stringent EPA-established Maximum Contaminant Levels as a guide.

For the Door County program, depending on the well or areas of concern, GZA is testing for PFAS, bacteria like coliform and E. coli, nitrates, arsenic, pesticides, personal care products, pharmaceuticals and microplastics.

Well depth is a factor in the study, because it is evaluating groundwater quality in a specific aquifer, within the Niagara dolostone, which is the uppermost dolostone bedrock unit, Stephenson said. Knowing well depth confirms that researchers are sampling the target aquifer, she added, and they are not sampling shallow wells, as the average well depth in the Niagara dolostone is about 240 to 260 feet.

There are gaps in available information on some wells, particularly older wells where paperwork is missing or records were not kept, she said. In those cases, researchers will talk to the homeowner to find out as much information about the well in question as possible.

Due to unusually dry conditions in fall 2023, one of the goals of spring 2024 testing was to resample the same wells to evaluate results after spring precipitation and melt, Stephenson said. Increased precipitation can lead to more surface contaminants reaching the groundwater or can dilute contaminants, causing results to go up or down, she explained.

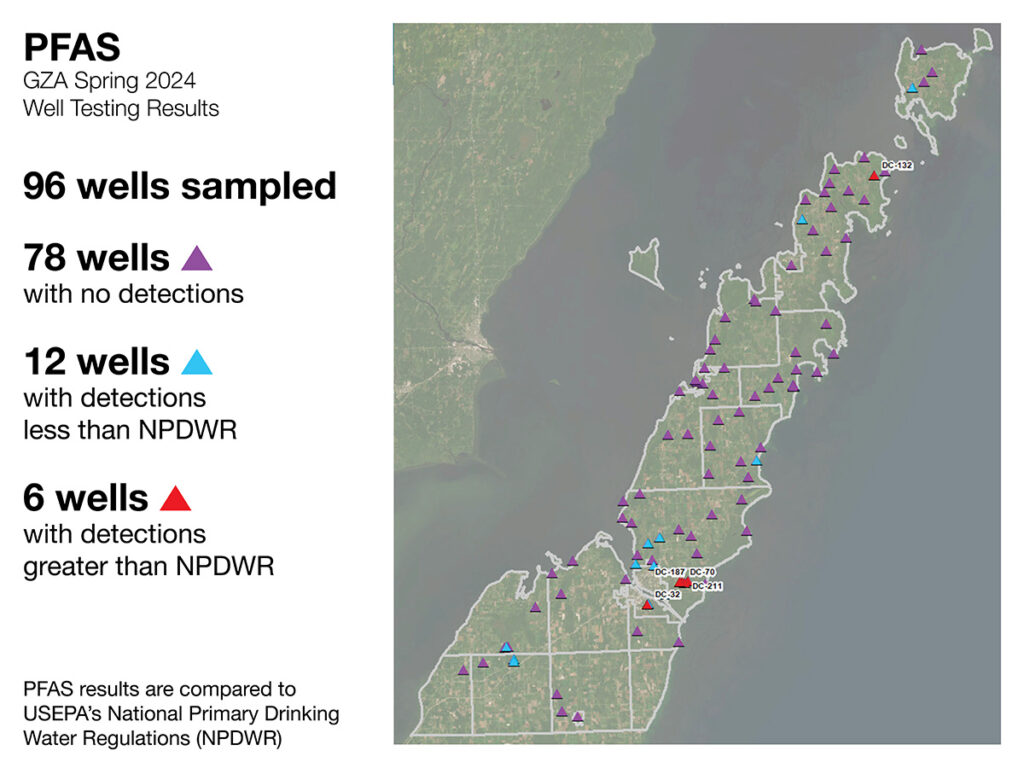

In addition to the “broad sweep” in spring 2024 that re-tested the first 89 wells, GZA also conducted localized sampling of wells in areas where contaminants were detected in fall. A total of 103 wells were sampled between June 3 and June 7, for both broad and localized testing.

Stephenson and her crew sent letters and in some cases, went door-to-door to get the localized samples. “(Sampling area) was dependent on who was home,” she added. “Not an ideal design.”

Spring detections of microplastics in northern Door County and PFAS in an area near Sturgeon Bay were the focus of the third round of samplings, according to Stephenson. Elevated levels of arsenic were also a focus in the third sampling event.

The number of samples taken so far probably does not fully represent the entire county’s groundwater quality, according to County Conservationist for the Soil and Water Conservation Department, Greg Coulthurst. The program must operate within its budget, he said.

Focusing on areas of suspected impact is the best way to get good data, Coulthurst explained in a phone conversation following Stephenson’s report to the board. “If you’re going to find something, you’re going to find them near these impaired areas,” he said.

Goals for the next round of testing taking place this spring have not been identified yet, Stephenson said, but the program will not be doing any more broad sweep testing. Rather, the program will focus on additional localized areas of concern, including PFAS, microplastics and arsenic detections.

PFAS

PFAS are chemicals that have been widely used in consumer and industrial products since the 1940s. There are thousands of PFAS chemicals and they break down very slowly, meaning they can be found in people’s and animals’ blood and are in a variety of foods and in the environment at low levels. Scientific studies have shown that exposure to PFAS may be linked to health problems in humans and animals.

The EPA began taking steps in 2021 to address PFAS groundwater contamination. One of those steps was investing money in groundwater testing and monitoring of public water sources. Door County’s Soil and Water Conservation Department is paying for the study with county-allocated American Rescue Plan Act funds. The study costs $357,700.

In the second round of testing last spring, GZA sampled 96 wells for PFAs and detected it in 18 of them, with 12 of those above EPA standards. One area in particular near Sturgeon Bay showed results anywhere from 3 to 7.5 times more than the EPA’s maximum contaminant levels of 10 parts per trillion.

“This likely represents areas where groundwater may be consistently above standards,” Stephenson said.

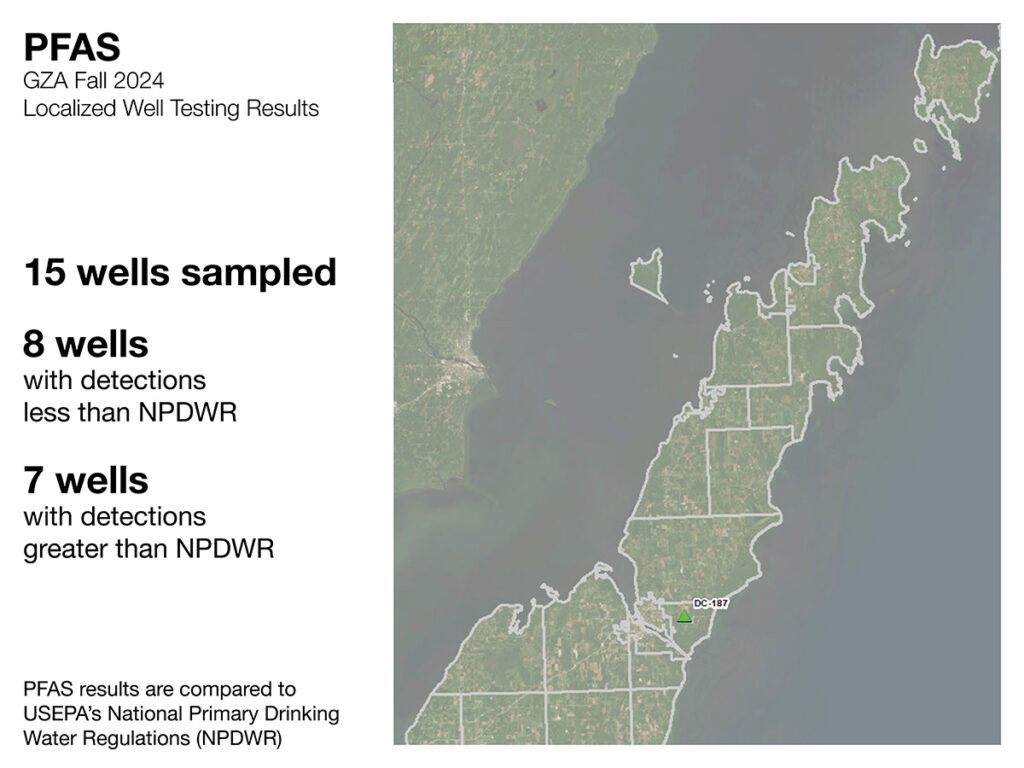

GZA looked even further into this area in fall 2024, sampling the four original wells, and 11 more for PFAS. All of them had at least one PFAS detection in levels higher than the EPA standard.

“We are certainly seeing more wells in this area that have exceedances,” Stephenson said.

Though fall 2024 testing results showed PFAS in that area remaining relatively stable, she said, the results indicate there was a source in the area that had an impact on groundwater. Results also indicate it is an area-wide issue and not specific to one well.

GZA will continue to study and monitor that area throughout the program, she said.

Microplastics

Microplastics are small particles that result from the breakdown of plastic. They are not regularly monitored and there are no published health standards to compare findings to, Stephenson said. Studies on microplastics in groundwater are limited, she added, and there is no standardized testing method for them.

“They are the definition of an emerging contaminant,” she said.

Some scientific research shows links between microplastics and human health problems, including inflammation, neurotoxicity and metabolic disorders. While research on the toxicity of microplastics is widely available, creating uniform standards and categories for them is difficult because of the wide variety of particle size, density and composition, according to the EPA.

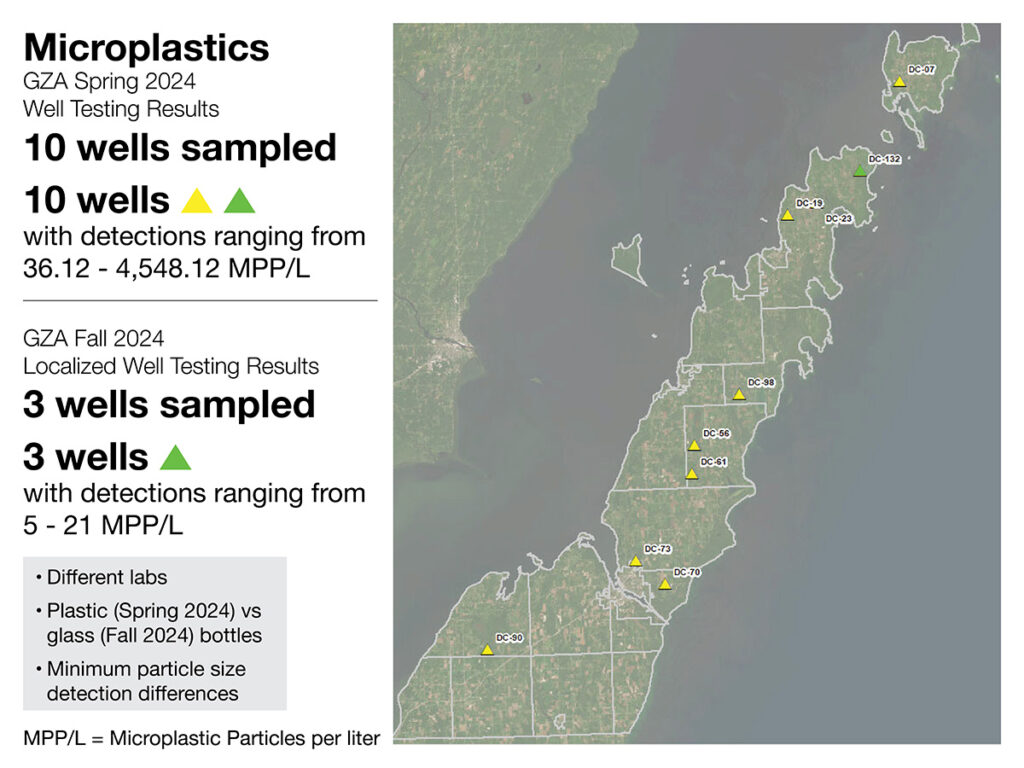

Spring 2024 testing of 10 wells showed all 10 with detections of microplastics, ranging from 36 to 4,548 microplastics per liter, or MPP/L. The well with 4,548 MPP/L was located in northern Door County and GZA returned to that area for more extensive localized sampling in fall.

Besides the original well, GZA sampled two more wells in that area. Microplastics were detected in all three, in amounts ranging from 5 to 21 MPP/L.

“Obviously the elephant in the room is why are these concentrations so significantly different than before,” Stephenson said. “This is still somewhat of a mystery to us.”

An aquifer that experiences a lot of variation in the groundwater that flows through it was one possibility for the difference, she said, but she offered another explanation. There is no national standard for how microplastics are tested, and the methodology is lab-specific, Stephenson said. GZA used two different labs from spring 2024 to the fall 2024 testing.

The lab in spring sent plastic bottles to collect samples and the lab used in fall sent glass bottles, she said. “They said there should be no interference … but that’s hard to know.”

Minimum particle size differs from lab to lab also, Stephenson explained. The lab from spring tests analyzed microplastics down to 6.5 micrometers, and in fall the lab looked at microplastics above 20 micrometers. For comparison, human hair has a width of 83 micrometers.

The smaller the microplastic particle, the more prevalent it is in the well, she said, and the samples taken in fall 2024 may have missed some of the microplastics detected earlier, in spring.

“It’s hard to have a reference for other studies when everyone’s using different lab methodologies that differ significantly,” Stephenson said. “Until we collect two samples side by side, it’s hard to tell what’s causing that discrepancy.”

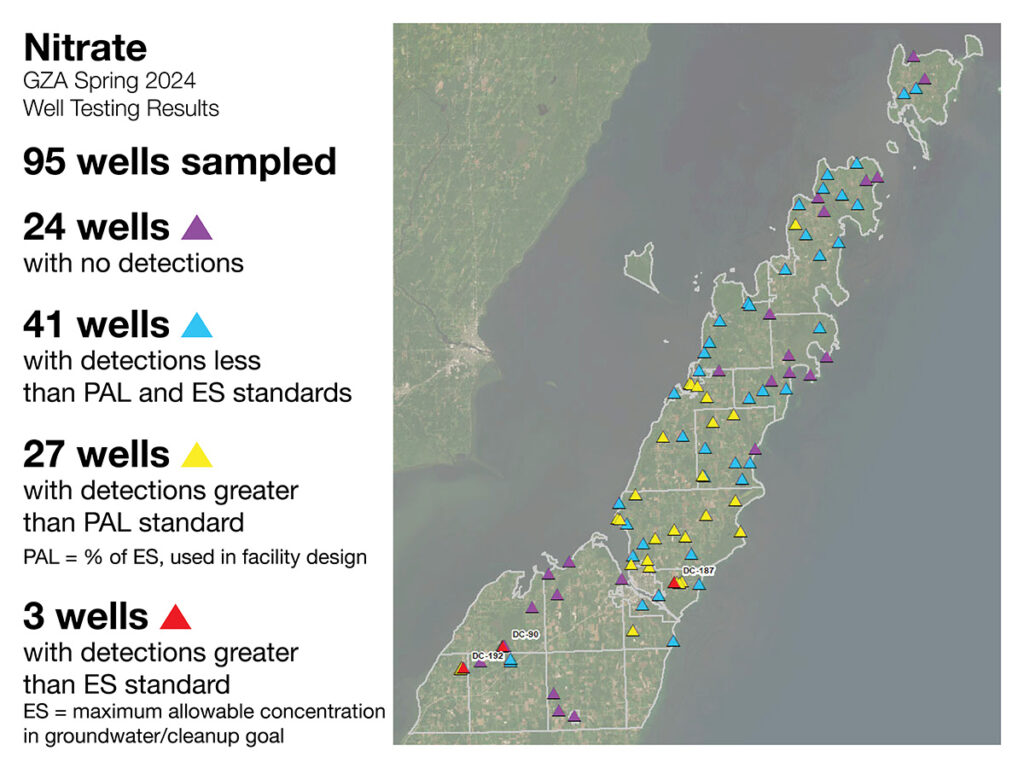

Nitrates

Typically a contaminant from agricultural fertilizer runoff, excess nitrates in surface water lead to toxic algae blooms and aquatic dead zones. In groundwater, nitrates can cause human health problems, and are especially harmful to pregnant women and infants.

GZA did not find alarming levels for nitrates, according to Stephenson, but localized sampling led to detections close to the standard 2 milligrams per liter, or mg/L, allowed by the EPA. All three of the wells with detections were downhill from agricultural fields, so these results indicate that agriculture may have an influence on nitrate concentrations in that area, she said.

There was one well that had a much higher detections of nitrate at 12.5 mg/L. That well also had detections of personal care products, pharmaceuticals, and PFAS, but the other wells tested nearby did not, Stephenson said. That indicates it may be localized human influence related to a septic system and the homeowner was contacted with results and information.

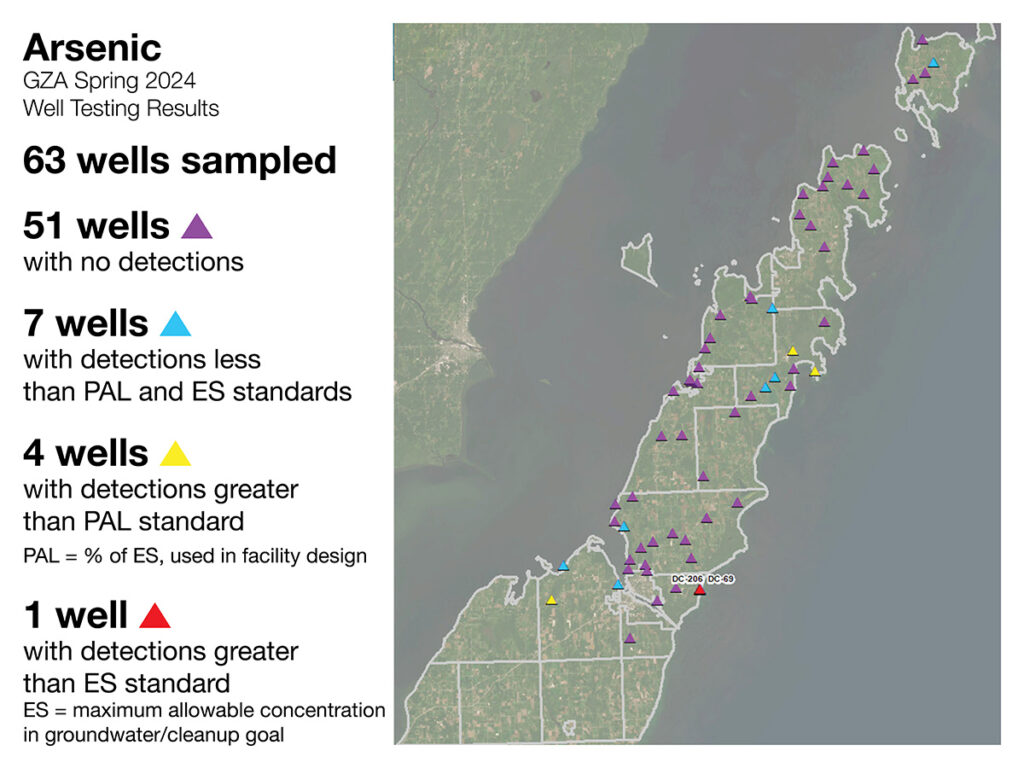

Arsenic

Arsenic is a naturally occurring element and can be present in groundwater from normal weathering processes of certain rocks. It is also a carcinogen that can get into groundwater from pesticides and herbicides.

Door County once produced almost 10 percent of the nation’s cherry crop, and the most commonly used pesticide in the cherry orchards from the early 1900s until 1988, when it was banned, was lead arsenate.

The county does not have a lot of concerns about lead arsenate contamination related to the cherry orchards, Coulthurst said. The wells that GZA found arsenic in are on the lake side of the peninsula, he said. If a well is going to have lead arsenate detections related to cherry orchards, they would be on the bay side, he added.

GZA found two wells that were “concerning” in the broad sweep in spring 2024. The EPA Maximum Contaminant Level standard for arsenic is 10 micrograms per liter. An amount of 25 micrograms per liter was detected in one well, and 27 in the other.

GZA explored the possibility that the higher concentrations were the result of the natural breakdown of certain carbonate rocks that release arsenic. The researchers tested for metals that accompany that process and found no trace, however, Stephenson said.

As a result, the program has more work to do in that area, she said, in order to discern whether it is a human source or influence causing the arsenic contamination. The area in question is just northeast of Sturgeon Bay.

The next sampling event will likely be spring or summer 2025, Stephenson said, and GZA will combine its results with those of another Door County well-monitoring project through UW-Oshkosh to determine the scope of those events. The county has a four-year contract with GZA, with plans for sampling events twice a year. The project is about halfway completed and GZA expects to perform at least four or five more sampling events in the spring/summer and fall seasons.

The GZA-led program had 173 volunteers throughout the county sign up to have their private well tested in the first round of sampling conducted in fall 2023. Of those volunteers, 89 wells were chosen based on land use, well depth, geology, topography and proximity to possible contaminant source areas such as landfills, orchards and airports. Testing is free and property owners receive a copy of the results.

The project may need more volunteer wells in specific areas and GZA will be conducting public outreach if that is the case, according to Stephenson. In the meantime, if property owners are interested in having their well tested, they can contact Coulthurst at Soil and Water Conservation directly.

At this point, the goal of the study is education, according to Coulthurst.

“The sooner people know that they might have an issue or they can do something about it, the better,” he said.

The county lacks data regarding groundwater quality and cannot make good decisions until it has more data.

“We don’t know what the end game is,” he said. “We’ll start forming that when we have a good picture of what’s in the water.”