Lake trout repopulation efforts have been ongoing since the 1950s and state commercial fishery representatives say it is time to open the commercial market for them so consumers have more access to a local food source.

But sport fishery and environmental group representatives disagree, arguing lake trout populations in Lake Michigan are not sustainable yet and pressure from commercial fishing would prevent the fish from reasserting themselves as a dominant Great Lakes predator. Opponents also say the current funding model for species rehabilitation means recreational anglers are paying for commercial fishery profits.

In September 2022, the Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board formally requested that the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources begin the rule-making process for establishing a Wisconsin commercial lake trout fishery in Lake Michigan. The process began with assembling a Lake Michigan Lake Trout Stakeholder Group to draft a statement of scope, or “scope statement.”

A scope statement establishes the framework for any rule the DNR is considering for implementation, including objectives, policies included in the rule, and how existing policies and entities may be affected by the future rule.

The stakeholder group consisted of Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board members, a Lake Michigan wholesale fish dealer, a restaurant owner that sells Lake Michigan fish, sport trollers and fishing guides, general anglers and sport fishing groups, the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation, the Wisconsin Conservation Congress, Wisconsin Sea Grant, and the DNR. The group held four meetings from February to May 2023 and a legislative hearing was opened to public comment on Feb. 13, 2025.

The next step is for the Natural Resources Board to either approve or deny the statement of scope as written. If the statement is approved, it will be drafted into a rule and economic impacts will be analyzed by the board before continuing along the DNR’s rule implementation process.

The scope statement regarding a commercial fishery for lake trout does not appear on the Natural Resources Board’s Apr. 9 agenda. The DNR is reviewing comments from the public hearing, including over 290 written comments the department received. The department is still determining how and if it will proceed with the scope statement, according to Kari Lee-Zimmerman, DNR program and policy analyst for fisheries management.

“If there are any substantive changes that we decide should be made to the scope based on the input we received, the whole process will need to go back to the beginning and start over,” Lee-Zimmerman wrote in an email. “If DNR decides to go forward with the scope statement as it currently is, the next step would be approval by the Natural Resources Board, but it is not an item on the April agenda since the next step determination has not been made yet.”

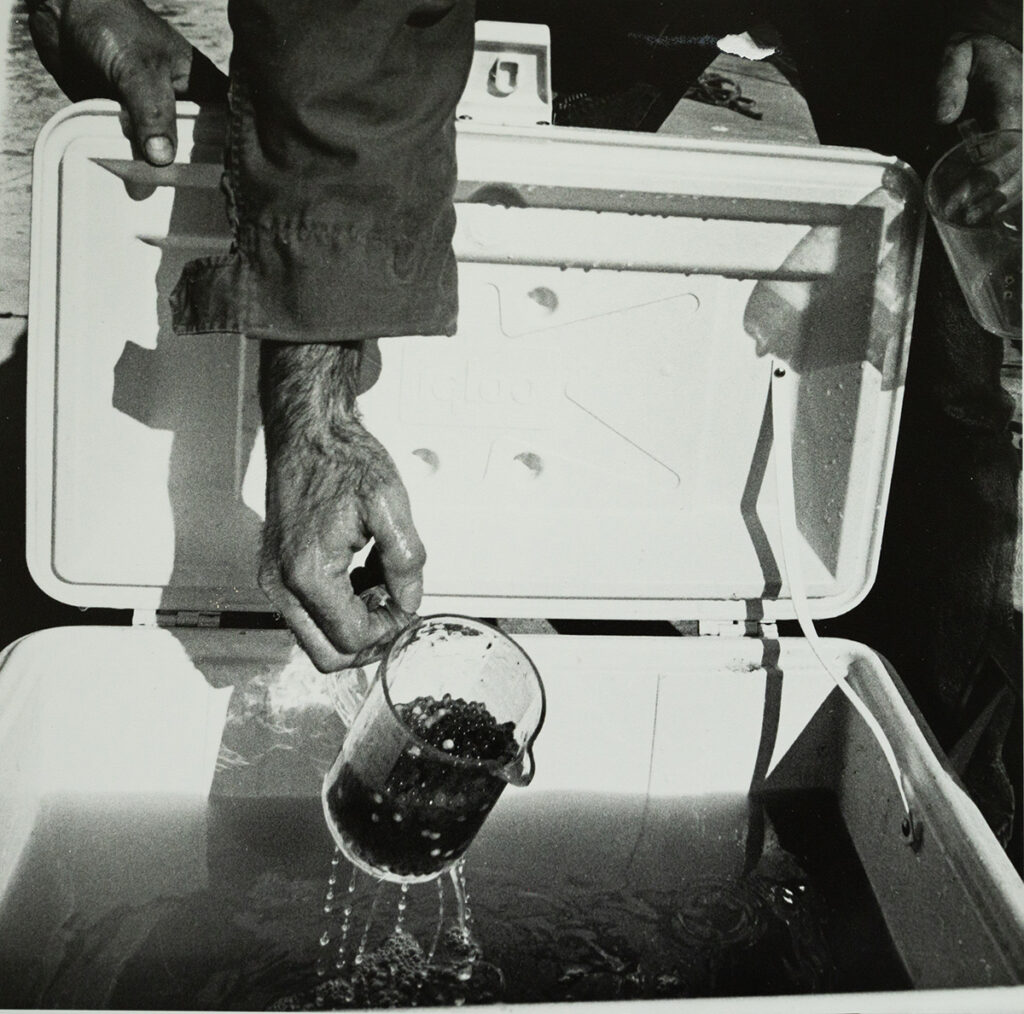

Other attempts at releasing fertilized lake trout eggs were made between 1973-81, with no evidence of successful reproduction, according to a 1992 research paper from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. In those early attempts, fertilized eggs were released without the turf shelters, according to the research paper.

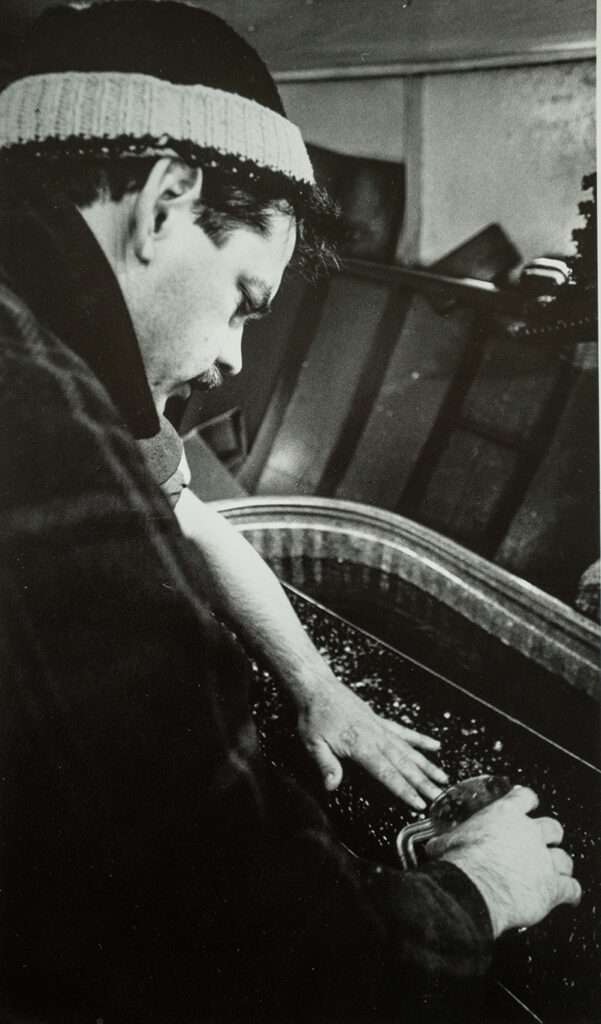

A search for results of the early 90s effort, pictured here, did not turn up any available research, or reveal if the eggs were brown trout or lake trout. But because the method is not currently in use, the results were likely not positive.

Over the years, most lake stockings have involved young fish, raised in stocking facilities, and released into the lake. Archive photos by Heidi Hodges.

Existing rule and proposed changes

The primary objective of the scope statement and proposed rule change is to establish a commercial harvest of lake trout in the Wisconsin waters of Lake Michigan.

Various topics may be addressed by the rule, including allowable fishing areas, season dates, total allowable catch of lake trout, percentage of total allowable catch that will go to the commercial fishery versus sport fishery, fish size limits, reporting requirements and more. The rule may also update sport fishery limits and regulations.

Right now there is no commercial fishery or market for lake trout. Sport anglers are allowed a “bag limit”–the amount of one species an individual can harvest in a day–of five lake trout with a minimum size of 10 inches. The sport fishing season for lake trout is open all year.

The current total allowable catch for lake trout is 48,443 fish per year, according to the DNR. The state’s sport fishery harvested 32,252 lake trout per year on average from 2019-2023. The Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board has requested that a portion of the total allowable catch be opened to the commercial fishing industry. The scope statement includes giving commercial fishers 20 percent of the total allowable catch.

Even 10,000 lake trout annually for commercial anglers would be welcome, according to Charlie Henriksen, commercial fisherman and owner of Henriksen Fisheries in Door County. Henriksen is a member of the Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board.

The DNR calculated the current total allowable catch by coordinating field surveys of lake trout with stocking and tagging data, genetic information, mathematical models and other data inputs.

The scope statement allows for this calculation to be updated and improved over time, which could impact total allowable catch in the future.

At the public hearing in February, Henriksen and other commercial fishery representatives expressed concerns over the language in the scope statement, indicating that it was not accurately reflecting commercial fishing interests.

“Our concern is that the mid level managers and the DNR put in a lot of policy on how that system is supposed to work,” Henriksen said. “The scope statement is supposed to open the discussion, not close off avenues of discussion.”

An example of limiting language, according to Henriksen, is that while the scope statement refers to “establishing a Lake Michigan lake trout commercial harvest” in the title, the first section narrows it to a “commercial bycatch harvest.”

Bycatch refers to fish that are caught incidentally, for example, lake trout that get caught in nets targeted for the commercial harvest of whitefish. Now commercial fishers return incidentally caught lake trout to Lake Michigan and report their bycatch numbers to the DNR.

Opposition from sport fishing and conservation groups

The funding model for commercial fishery management and concerns about the sustainability of the lake trout population are the two main arguments used by those opposed to a commercial lake trout harvest.

The DNR uses funds from its fish and wildlife account to support the department’s fish and wildlife management, including commercial fishing activities.

This is not fair, according to recreational fishing and environmental opponents of a commercial fishery for lake trout. Wisconsin’s Green Fire, an environmental group wrote in their statement: “The private profits generated by commercial fishing on the population, whose recovery has been funded almost entirely by recreational fishers, would benefit the industry exclusively. Making a private profit from a public resource that others are still paying to produce is not a fair approach to fishing…until the cost burden of commercial fishery management is distributed fairly relative to the benefits of the harvest produced, the fishery should not open.”

License fees, including commercial ones, were last raised in 2017.

Lake trout are a predator fish, native to the Great Lakes, that can reach up to 40 pounds or more in maturity. They are a slow-growing fish, and by 1945, the population collapsed due to overfishing and an invasion of the non-native sea lamprey, according to the DNR.

Extensive efforts to rehabilitate Lake Michigan’s lake trout population include sea lamprey control, stocking lake trout and controlling lake trout mortality, according to the scope statement.

Lake trout populations have started to recover, but with limited natural reproduction in Wisconsin waters.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is responsible for restocking efforts that have poured 300 million lake trout into the Great Lakes in an effort to repopulate the species, according to a USFWS report.

“While available evidence does show that lake trout populations in Lake Michigan are headed in the right direction, it does not yet strongly indicate that populations can sustain themselves against mortality from natural, recreational, and commercial sources,” according to Green Fire’s statement.

“What is bycatch today often becomes a target tomorrow when it is commercially prized and newly legal to harvest,” the statement said. Even limiting the commercial fishery to bycatch of lake trout could have a negative impact on the population.

There are no provisions to protect against incentivized commercial lake trout harvest within the scope statement, Green Fire concluded.

Additional strain on the lake trout population is also a concern of recreational anglers.

According to the scope statement “if the sport total allowable catch is exceeded in any one year…[it] could result in bag limit reductions and season changes in the following year” and “depending on how the total allowable catch is allocated between sport and commercial fishers, this may also limit the ability of sport fishers to harvest lake trout without additional regulations.”

This language means the recreational fishing industry has a good chance of being limited if the total allowable catch is exceeded in any year by commercial or recreational industries, according to a joint statement by the American Sportfishing Association and the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation.

Opponents of the rule also said recreational fishing has a much higher economic impact and value than commercial fishing and should be prioritized when it comes to making decisions that will affect the fishery.

Local commercial fishing industry supports rule but not scope language

By not allowing a commercial harvest of lake trout, consumer voices are being ignored by the DNR, according to Henriksen and other commercial fishery representatives. Consumer voices are almost always left out of fishery management decisions, Henriksen said, and he would like to see that change.

Several Door County residents and business owners submitted written comments for the DNR scope statement hearing. Most of the comments received from Door County were in favor of a commercial fishery for lake trout.

Destination Door County’s Communications Officer Jon Jarosh wrote: “From a Door County tourism standpoint, the commercial fishing industry has and continues to play important roles in both our destination experience and in our local economy…lake trout would play a big role in providing new experiences for residents and visitors to enjoy fresh fish on restaurant menus for this renewable and local resource. Consumers would like their voices considered in this matter.”

Pat Fuge, co-owner of the Gnoshery restaurant in Sturgeon Bay, supports a commercial fishery and wrote, “our livelihood and lifestyle are tied directly to the proper management of the resources and quality of the Great Lakes, and the fish that swim in them. A commercial lake trout harvest to give all the people of Wisconsin access to this fresh, local renewable resource is long overdue.”

According to Carin Stuth, co-owner of Hickey Bros Research and Baileys Harbor Fish Company in Door County, this access to commercially caught fish is critical, as not everyone in Wisconsin can pay for a fishing charter or launch a boat to catch lake trout.

“The commercial fishery is providing these fish to the residents of the State of Wisconsin, and beyond, as a food source,” Stuth wrote in her statement to the DNR.

However, a Spring Hearing Questionnaire performed annually by the DNR’s Wisconsin Conservation Congress said there may not be much of a public appetite for lake trout. The survey is performed in advance of the Congress’s spring meeting, and it asks a number of questions related to potential and existing conservation policy.

In 2024, the survey had 18,802 respondents, according to the DNR . Of those respondents, 2,154 support a commercial lake trout fishery, 7,516 do not, and 6,206 had no opinion. Door County was the only one of the state’s 72 counties that in-person respondents supported a commercial lake trout harvest.

Online and in-person, there were 1,591 total respondents for Door County. In-person respondents who stated they were residents of Door County were in favor of the measure 43 to 36 with 12 respondents having no opinion. Of online respondents who indicated they recreate in Door County showed 228 in favor, 688 opposed, and 267 with no opinion.

Door County’s history and culture is tied to commercial fishing and as a result, “the general public pays attention,” Henriksen said. Door County is also where the largest portion of the commercial harvest in Lake Michigan happens in Wisconsin.

Henriksen said he thinks the Conservation Congress survey is not a reliable indicator of public opinion because “it plays to a limited audience and is easily influenced by its leaders and DNR staff,” he said.

Proponents of commercial fishing also said the industry is not widely understood, and legal fishing zones, fishing techniques, or times of year commercial fishing is allowed are already heavily regulated.

Fishery management by the numbers

The state’s commercial fishing economy is much smaller than its recreational fishing economy.

Recreational boating and fishing generated $710 million in Wisconsin, according to a 2022 report from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The American Sportfishing Association, in conjunction with Southwick Associates, a market research and economics firm specializing in outdoor recreation markets, released a recreational fishing economic impact report in 2022 that found 1,366,450 resident and non-resident anglers spent $2.4 billion while fishing in Wisconsin. That number includes money spent on anything related to sportfishing, such as licenses, gear, docking fees, lodging and more.

In contrast, the commercial fishing industry in Wisconsin, which includes those who fish Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, generated about $4.7 million last year, according to Miranda Westphal, the DNR liaison to the Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board.

A maximum of 65 commercial fishing licenses are available for the Wisconsin waters of Lake Michigan, Westphal said, and in 2025, 34 fishers hold 48 licenses (a commercial fisher can hold more than one license).

In addition to individual anglers, bait and tackle shops, boat rentals, lodging and fishing tournaments or other businesses related to recreational fishing, there are more than 50 charter fishing businesses in Door County alone.

According to records from the DNR’s Bureau of Management and Budget, in 2022, commercial fishing license fees generated $53,100 in revenue. About $700,000 was spent on commercial fishery management, according to the records.

Many license fees, including commercial license fees, were raised in 2017. For non-resident license holders the cost went from $300 to $420. For residents, the fee was raised from $50 to $70.

Though total recreational license fee data was not available, data from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service shows that in 2019, 1.3 million in-state and out-of-state anglers bought a fishing license in Wisconsin.

An annual recreational license for a Wisconsin resident is $20, and $55 for out-of-state anglers, and Gov. Evers proposed a 20 to 40 percent increase in fishing license fees in his most recent budget proposal.

Commercial fee funds and sport license dollars pay for 92 percent of commercial fishery management, according to a 2017 fisheries report from the DNR.

Beyond money

The current Wisconsin commercial fishery is much smaller than it was 100 years ago, according to Henriksen, but it has lasting cultural impact, especially in Door County.

“The legislature and the DNR understand our (commercial fishers’) contributions go beyond just licensing fees,” Henriksen said, indicating the industry provides invaluable information about fish populations and health, as well as taxes for fuel, equipment and more, and none of that is calculated as part of the fish and wildlife fund.

Door County is home to the bulk of the commercial fishing businesses that are left, many of them family-run operations that have been passed down from generation to generation. Understanding the history of commercial fishing is important in order to effectively regulate it today, Dennis Pantazis said.

Pantazis is a recreational angler, a member of Salmon Unlimited and has been fishing in Door and Kewaunee counties since the 1990s. He also comes from a family of Greek commercial fishermen.

He submitted a statement during the Feb. 13 hearing that he said comes from having a foot in both the commercial and recreational fishing industry camps: “Commercial fishing of the Great Lakes is part of our collective heritage. No dollar amount can be assigned to this. While the monetary value of commercial fishing is dwarfed by the monies spent in the recreational and charter fishing activities on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, it is an equally important use of our natural resources.”

Pantazis said he thinks a middle ground can be reached, and “it appears that establishing a legitimate by-catch fishery may be appropriate for consideration, but I believe promotion of this rule as it is currently written will set a bad precedent for future decisions.”

The scope statement and subsequent rule is lacking clarity and needs to be written with better scientific data and the input of all stakeholders, Stuth from Baileys Harbor Fish Company said, in order to set a solid foundation for fishery management going forward.

Regardless, all stakeholders seem to agree that the reestablishment of the lake trout population is critical for Lake Michigan. Whether those efforts will include a commercial fishery for lake trout remains to be seen.