March brought bad news for food pantries and school food programs after federal cuts, to the tune of more than $1 billion, were made to a handful of U.S Department of Agriculture programs that served pantries and schools nationwide, including those in Door County. The cuts were made in the middle of the grant cycle, stopping money that was already contracted to various state agencies who administered the funds.

The Emergency Food Assistance Program, Local Food Purchase Assistance, and Local Food for Schools were all cut in early March, as part of the Trump administration’s movement to reduce government spending.

TEFAP, LFPA and LFS were developed as a way of shoring up and strengthening local food systems, providing local, nutritious food to food pantries and schools, and helping marginalized populations of growers and producers access food markets, after supply chains were interrupted during the Covid pandemic, according to a USDA press release in 2021. All three programs were funded through the Commodity Credit Corporation, established by the federal government in 1933 to stabilize farm markets and facilitate the distribution of agricultural products.

On March 7, pantries received notice from the USDA that their food deliveries through the TEFAP would be cut in half by May, according to Sandi Soik, Lakeshore CAP food pantry director. In April, the pantry had already seen a 20 percent decrease in deliveries through the program, she said.

It was a double whammy for CAP, as they were also the recipient of LFPA funds. LFPA provided $13,400 in fresh, local food to a few Door County pantries in 2024.

Lakeshore CAP, in Sturgeon Bay, is the largest food pantry in Door County, serving over 500 pantry customers a month in 2024. Out of the nine pantries that belong to the Door County Food Pantry Coalition, CAP and the Washington Island Food Pantry are the only ones who receive federal funding through the USDA, and they keep careful records of how much food goes in and out of pantry shelves.

LFS was also terminated in March. The Sturgeon Bay school food program received $26,000 of the $800,000 LFS grant dollars used statewide, according to Jennifer Spude, the nutrition director for the Sturgeon Bay school food program.

On the flip side, growers, farmers and businesses that were providing fresh, local, nutritious food to pantries and schools were also affected by the sweeping cuts. Nearly a dozen Door County providers were involved in some capacity with the USDA programs, whether as a grant recipient or a food provider to a grant recipient.

Miranda Hottenroth, a local farmer who leases growing land, was an LFPA recipient in 2023 and 2024. She recently switched gears from farming to food truck, in order to raise enough money to purchase her own land, she said, but she knows what the program meant to her as a farmer, and what it meant for the local food landscape as a whole.

As a recipient of the program for its first two years, Hottenroth said she saw local food systems really start to figure things out, building and tweaking things like distribution, logistics and packaging.

“I feel like 2025 would have been an even better year, a little bit more efficient in the launches and navigations, and the collaboration between farmers, transportation, distribution, hubs and access points,” she said, and her hope is that the Wisconsin legislature sees the value of the the programs and keeps momentum going by including them in the state budget somehow.

The USDA programs that were cut were never meant to be long-term federally-funded programs in her understanding, she added, but they were meant to continue through the end of 2025 at least.

The abrupt cessation of the program will increase dependency on private donors and corporate generosity, according to pantry and school representatives, as well as decrease access to local, nutritionally-dense food for schoolchildren and food insecure populations.

But one local farmer, Jacob VandenPlas from Door County Farm for Vets, feels it’s time to take local food production “to the next level,” and said community- and self-reliance is the answer when the government cuts funding to programs like this.

Overview of programs

TEFAP was established in 1981 to distribute surplus agricultural products to food insecure households. In 2021 the American Rescue Plan Act provided additional funding to the program as part of the Biden administrations’ Build Back Better Food System Transformation Initiative. That additional funding was cut by the current administration.

At the federal level, TEFAP is administered by the USDA which purchases agricultural products and distributes them to states. State and local public health departments and food banks then distribute the USDA foods to pantries and food programs.

In March, the USDA cut $500 million intended for food banks in 2025 and 2026, according to Carol Johnson, Emergency Food Assistance Program coordinator at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ Division of Public Health.

In Wisconsin, months’ worth of orders already placed by food banks and pantries have been canceled as a result of the cuts, she said, and the deliveries impacted were to arrive May through September 2025. The cancelled shipments totaled $2.2 million dollars and about 1.1 million pounds of products, including milk, eggs, cheese, pork chops, chicken and turkey breasts, according to Johnson.

Lakeshore CAP and the Washington Island Food Pantry have already seen a 20 percent decrease in April for USDA food received. This translates into cutting back on food allotments for families, Soik said. Both Soik and Washington Island Food Pantry co-director Dan Westbrook said they would also lean more heavily on local private donors to make up the gaps.

The LFPA program was a cooperative agreement between the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service and Wisconsin’s Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, initiated in 2021. It was designed to strengthen local food systems and get nutritious and fresh food from Wisconsin producers to food insecure populations.

LFPA grants were administered in a two-prong approach. Food pantries and other distribution centers could receive grants to purchase fresh, local, minimally processed food for food insecure patrons. Farmers and producers could also receive grants to expand their wholesale reach to those food access programs.

Hottenroth’s Backyard Acres was one of two small Door County farms that received grants as producers, as well as Lakeshore CAP as a distributor. In total, $13,400 worth of food was delivered to pantry shelves in Door County through LFPA in 2023 and 2024.

A $5.48 million cooperative agreement was signed for 2025 and 2026 in Wisconsin. The agreement, referred to as LFPA25, was what was terminated in the beginning of March, according to Kelly Mella, DATCP’s public information officer.

That the agreement “no longer effectuates agency priorities” was the only explanation given by the USDA for the termination.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction received almost $3.5 million from the USDA through the LFS program, a sibling to LFPA meant to get local and minimally processed foods to school breakfast and lunch programs and childcare centers.

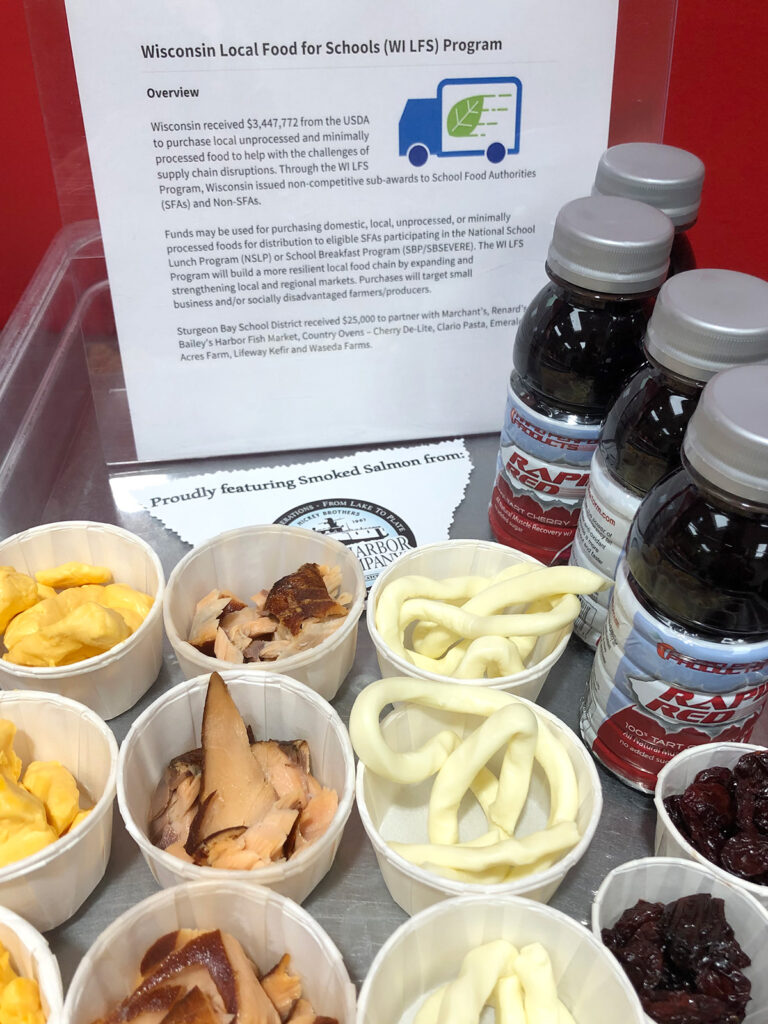

Thanks to the LFS grant they received in 2023, the Sturgeon Bay school food program was able to partner with several Door County producers, including Emerald Acres Farms, Clario Farmstead Pasta, Renard’s Cheese, Country Ovens and Baileys Harbor Fish Company, Spude said, and it strengthened existing relationship with Jorns’ Sugar Bush and Waseda Farms.

The Sturgeon Bay school food program provides food service to all public schools in Sturgeon Bay, as well as St. John Bosco Catholic School and the Head Start program. By the end of last school year, 10 percent of the program’s food was purchased locally, according to Spude.

USDA representatives did not respond to requests for comment on the cuts, but in a FOX News interview on March 11, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins called the programs Covid-era expenditures that are “nonessential.”

Necessity and scarcity

Fresh, nutrient-dense food like produce and quality proteins are essential to a healthy diet, and those kinds of foods are at a premium in most food pantries because they are costly, FoodWise Coordinator Laura Apfelbeck said. FoodWise is a UW-Madison Extension program that serves low-income people, providing education on choosing healthy diets, preparing nutritious food, and becoming more food secure.

“Walk through a local food pantry and imagine what you’d make for dinner,” Apfelbeck said in a phone conversation. The reality is that many of the low-income families and individuals served by FoodWise are also pantry users that depend heavily on the food they get there, she said.

“Okay, your choice of three vegetables, two fruits, two proteins and carbs, breads or tortillas or whatever – what are you going to make this week with what you can take?” Apfelbeck said. Throw in allergies, intolerances and other diet factors and she said it’s challenging to eat at all, much less eat healthfully, if one is dependent on a food pantry, she explained.

Low-income people are also the least likely to have access to quality medical and dental care, Apfelbeck said, making it even more crucial to have healthy food available to them.

Fruits and vegetables fill many nutritional and dietary needs, she said, but they have a relatively short shelf life, are costly, and are not usually the items commonly donated unless pantries sponsor targeted food drives for them.

“That was such a great benefit of these programs,” Apfelbeck said. “Pantries were able to acquire them at minimal (financial) risk.”

Pantry use has increased in the last few years. Lakeshore CAP has seen at least a 24 percent increase in pantry use from 2023 to 2024. Food prices continue to rise and wages are not keeping pace with inflation, Apfelbeck said.

Similar roadblocks exist in getting fresh and nutrient-dense products to school food programs, according to Spude. She is a registered dietician who said she is passionate about developing children’s palates for healthy food and school lunch is one way to do that.

Sturgeon Bay High School has a greenhouse that provides some fresh produce to the food program, she said, and the greenhouse was one of the biggest LFS participants locally. Kale, cherry tomatoes and some herbs grown there were purchased with the LFS grant money received by the school food program, putting that money back into the greenhouse and the educational programming built around it, Spude explained. That produce was then served “right on the lunch line,” she added.

Working with local growers and producers takes a lot of extra legwork for a school food service program, Spude said, and the LFS program incentivized those kinds of partnerships. Spude said she will continue working with the local food producers she has established relationships with, though the loss of LFS funding means local foods are already showing up less frequently on the menu.

“We offer fresh fruits and vegetables (instead of canned) twice a week and the amount now is just significantly less,” Spude said. “We used to have a nice selection, and now it’s a little bit lackluster already. That makes me sad, as a dietician.”

Emerald Acres Farm of Door County is a sustainable vegetable farm that does most of its business through a 50-member community supported agriculture program, farmer’s market sales and selling small wholesale quantities to local restaurants, grocery stores and schools.

Valerie and David Boyarski started Emerald Acres in 2013 and expanded in 2017. They use sustainable and regenerative farming practices to grow their produce. They raise goats and chickens as well.

Emerald Acres has been working with Spude the last two years, according to Valerie, and the business was planning to ramp up that relationship this year. Though Emerald Acres was never specifically contracted through the LFS grant process, the school food program scaling back purchases indirectly impacts their bottom line, she said.

Emerald Acres had purchased seed and factored school food purchases into their planting schedule for the 2025 season, she added. Meeting the needs of kids in the school food program is important to the couple, regardless of funding.

“We can continue to work together, on some level, maybe with less quantity,” Valerie said. She described Spude as dedicated.

“She’ll find a way,” she added.

Food pantries will try to find a way as well. Local donor generosity is remarkable, according to both Soik and Westbrook, and both CAP and the Island food pantry will try to make up gaps from TEFAP and LFPA cuts by increasing food purchases using funds from pantry benefactors.

Corporate donations through a contract with Feeding America are also a source of some nutritious foods for the pantries, according to Soik. Walmart, Pick ’N Save, Target, Kwik Trip and Starbucks donate food to CAP. Produce and meat are a large part of those donations, she added, but the pantry has little control over what items they receive as it is based on the ebb and flow of stores’ inventory.

Pantries also have relationships with local farmers and gardeners outside of LFPA grant contracts, Soik said. Door County Farm for Vets donates produce, a local hydroponic garden provides winter lettuce and household gardeners bring their harvests when they have extra.

Community and self-reliance

Jacob VandenPlas runs Door County Farm for Vets with a handful of other military veterans and spouses. The nonprofit is a rehabilitation farm that provides education and programming to help veterans grow their own food. VandenPlas also ran as a member of the Libertarian Party in the 2022 general election for the U.S. House to represent Wisconsin’s 8th Congressional District. He did not win the seat.

Farm for Vets was not an LFPA or LFS grant recipient, but the organization works with local food pantries, VandenPlas said, and received another federal grant this year for livestock fencing on their 40-acre property near Sturgeon Bay.

VandenPlas said he is grateful for the federal money, but “there’s absolutely nothing that happens that is eternal when it comes to these government programs. They’re intended to help. Maybe they’re going to do good, but you can’t count on that to be here tomorrow.”

“But what we can count on is our neighbors to come together to help support each other. And that’s how the problems, like food insecurity, end up getting solved,” he said.

The ultimate mission of the farm, VandenPlas said, is to combat veteran suicide. They have recently expanded their mission to include first responders in the organization’s outreach, he added.

“Suicide rates for veterans are through the roof,” VandenPlas said, and he believes growing your own food and working the land can improve mental health outcomes.

“Self reliance gives you a sense of control and peace back over your life,” he said.

That philosophy extends beyond veterans and first responders, he added. If it were up to VandenPlas, Door County’s local food infrastructure would be stronger and more interdependent, and his executive board is working toward that concept.

This year, Farm for Vets is launching a Victory Garden initiative where participants will learn to grow enough produce to fill their freezers and pantry shelves for the year in one 20 by 50 foot, or in some cases 20 by 20 foot, space. The organization also provides education on succession planting, soil regeneration, butchering and processing livestock and other skills. VandenPlas said a return to this kind of food production would alleviate much of local food insecurity.

Victory Gardens were a widespread practice during World War II, where Americans were encouraged to grow their own food in response to food shortages and to contribute to war efforts. Gardens sprouted up in backyards, parks, even rooftops, and provided 40 percent of the fresh fruit and vegetables consumed during the war, according to the USDA.

Having land or space to garden is a privilege many people do not have, VandenPlas acknowledged, and he encourages renters to grow things in containers or raised beds. Farm for Vets has unused acreage also, he added, and the idea of community gardens hold possibility for people who do not have the space to plant a garden.

Neighbors can work together too, VandenPlas said. One person can plant 10 zucchini plants and have enough for the entire neighborhood.

“We’ve got to rebuild our communities, and we can do that through gardening,” he said.