This story was produced and originally published by Door County Knock in collaboration with Wisconsin Watch, which is reporting on measles statewide. It was made possible by donors like you.

Washington Islander Pam Goodlet was 13 when she contracted measles in 1963. “I was ill and bedridden for weeks,” she remembered. “When I was finally able to get up, I was a skeleton. My pants couldn’t stay up and my clothes hung on me.” The severity of the illness is still fresh in her memory, and she is grateful she did not have any long term health consequences from the disease, as others in the area did.

Others were not so lucky. Melanie Bauer lives in Sturgeon Bay now and spent a lot of time in Door County throughout her childhood. She was born in 1957 and was very young when she had the measles. She does not remember being sick, but she does remember finding out she was deaf in one ear as a result of the disease.

“My dad was talking to me on the phone, and he said to put it to your other ear. I heard nothing,” Bauer said. “They took me to an audiologist who said the nerve is shot, and it’s not curable. The audiologist said I’m lucky and most of the patients they have seen are deaf in both ears.”

Hearing loss is one of the most common long-term health effects of measles. Before measles vaccination was widespread, the disease caused 5 to 10 percent of profound hearing loss cases in the U.S., according to the National Institutes of Health.

The CDC declared measles eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, but that is no longer the case. There have been more than 1,333 reported cases of measles in 41 states this year, including Wisconsin. That is the most in 33 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services confirmed nine cases of measles in Oconto County on Aug. 2. All nine of the cases were exposed to an out-of-state source while travelling. DHS and Oconto Public Health said they are working to notify people who may have been exposed and the risk to the community is low.

Door County, as a tourist destination, could be particularly at risk for an outbreak because of the influx of people from all over the U.S., according to Door County Public Health officials.

Not a ‘normal’ childhood disease

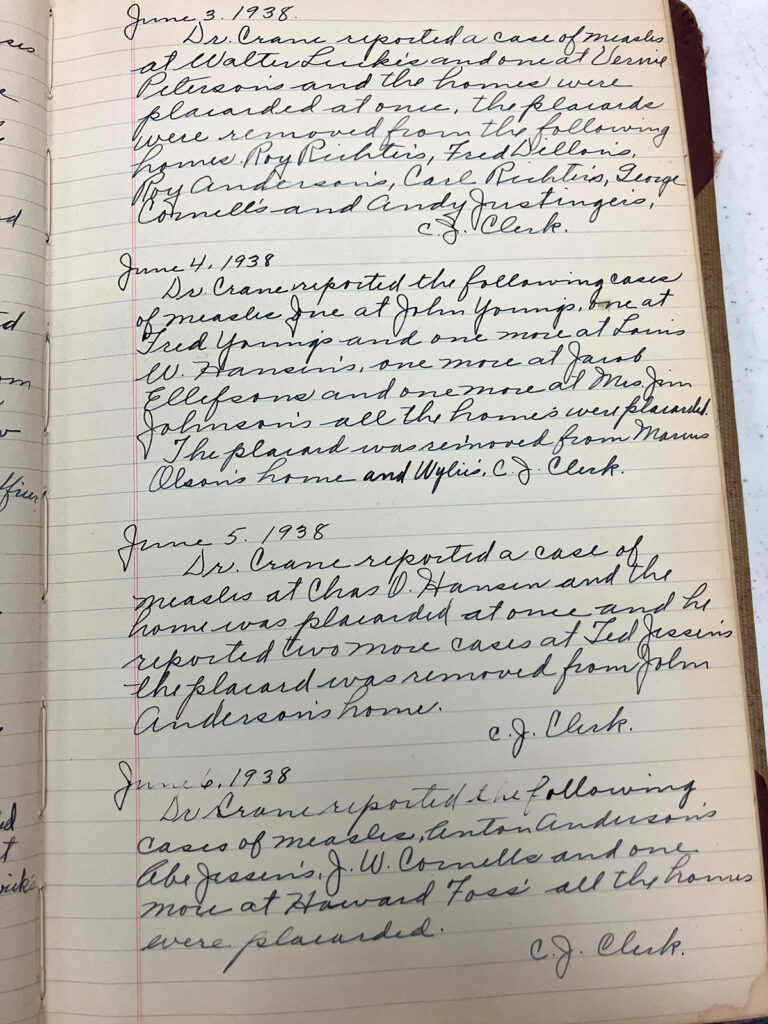

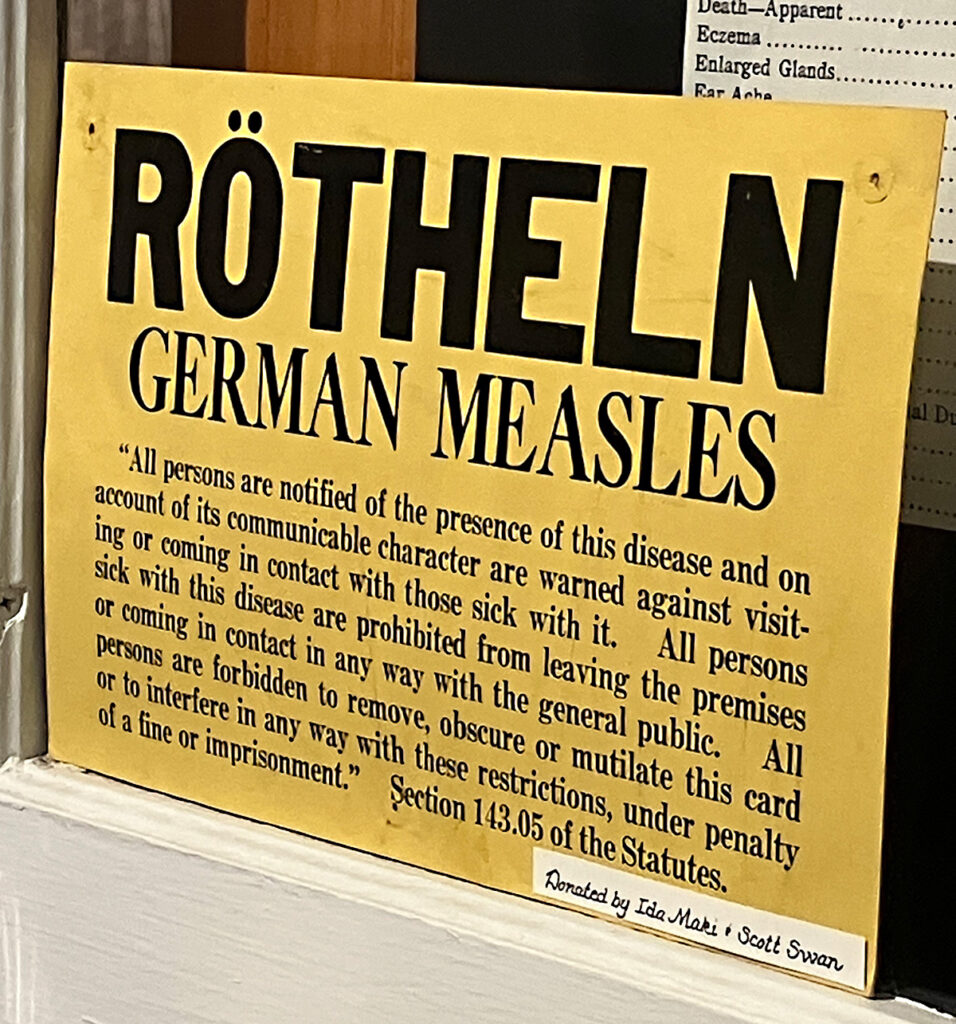

Before the measles vaccine became available in 1963, the disease was common. Most people contracted the measles when they were children, along with other illnesses like scarlet fever, whooping cough and chickenpox. Measles is one of the most contagious of all infectious diseases, according to the CDC. This was illustrated by an outbreak on Washington Island that lasted from May through December 1938.

Well over 150 cases were recorded by the Washington Island Board of Health in that time. For comparison, outbreaks of scarlet fever and chickenpox in a similar time period only produced a dozen or so cases. In 1938 the Island population was close to its current number of 718 people. There were 738 residents in 1940 and 784 people a decade earlier, according to census information.

“Measles can be a dangerous disease. It is highly contagious and runs through susceptible communities rapidly,” Dr. Todd Reynolds, a family medicine physician at Prevea Health in Green Bay, said in an email. Reynolds has been practicing medicine for over 40 years and said he has diagnosed and treated measles in that time.

Potential long term health complications from the disease are serious, according to Reynolds, and as many as 30 percent of cases result in complications like dehydration, pneumonia or encephalitis. Encephalitis, or brain inflammation, can be very serious, with symptoms ranging from flu-like illness to severe problems like seizures and coma.

Additionally, “measles causes host immune suppression allowing secondary infections from other pathogens to occur which can be minor or severe,” said Reynolds. “Since measles can cause secondary immune suppression, there are reports where immune function has not returned to 100 percent after recovery. There is a rare condition known as subacute sclerosing pan encephalitis that is a fatal neurologic degenerative disease that can occur 7 to 10 years after a measles infection. There is no known treatment.”

Treatment and response

Pam Goodlet was lucky and did not suffer lasting complications from her measles infection. Though covered head-to-toe in red blotches, bedridden for weeks, delirious from fever, and unable to eat or drink water—she sucked on ice cubes for hydration—Goodlet said she only received one visit from the island physician and was never taken to a hospital or clinic.

“Back then, you just didn’t,” she said. Most people who were ill recovered at home and relied on home remedies for treatment.

That does not mean health professionals in the past were unaware of the seriousness of measles. Public health officials produced bulletins and newspaper articles to spread the word regarding its dangers.

“Of all of the communicable diseases, measles is one of the most contagious,” declared the Medical Society’s health bulletin in a Dec. 10, 1931, issue of Door County News. Another bulletin from 1932 said, “And worst of all, measles kills more children in the United States every year than either scarlet fever or diphtheria, both of which are more greatly dreaded.”

A Door County Advocate health bulletin published on August 29, 1967, reported:

“Red measles, known medically as rubeola, is not a ‘normal’ childhood disease or ‘something that they’ll catch anyway.’ This disease may be severe and occasionally result in severe complications. Pneumonia is the most frequent complication. Ear infections which may result in hearing disorders are not uncommon. The most dangerous complication is encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain.” The bulletin also referred to cognitive impairment as a potential long-term consequence of encephalitis.

Medical professionals in Door County called on the community to isolate to stop the spread of measles. A bulletin in the Door County Advocate published in April of 1963 referred to “measles and flu really making the rounds…especially the childhood disease, measles, is quite prevalent.”

Goodlet caught her measles infection during an outbreak that was described by the Advocate in 1963. The newspaper reported graduation ceremonies and a church-sponsored Bible school were postponed during the outbreak.

The message to stay home was not always heeded, however, Goodlet said. She remembered traveling to the mainland with her classmates in June 1963 to celebrate their eighth grade graduation with Gibraltar students. All students attended, with the exception of one who was home with the measles, she said. By the end of June her entire class ended up contracting the virus, she said.

Dr. Reynolds explained that it is possible to be contagious with the measles before symptoms begin. “There may be no warning signs that you have been exposed to measles,” he said. The incubation period of the disease is one to three weeks before symptoms occur. Initial symptoms include fever, malaise and poor appetite, and persons with the measles can be contagious five days before the telltale rash occurs, he said.

Measles is airborne or spread through contact, and the transmission rate is 90 percent, according to Reynolds.

Prevention and falling vaccination rates

As far as measles prevention, “the most effective tool we have is immunization,” said Reynolds. “The measles vaccine currently available is safe and highly effective but requires commitment and cooperation.”

Community vaccination rates have dropped nationwide since the Covid pandemic, including in Door County. Voluntary exemptions for personal and religious reasons have risen as well, according to a report by the CDC in October 2024. Wisconsin is one of 15 states that allows for personal and religious exemptions to school vaccine requirements.

When vaccination coverage decreases and exemptions increase, the risk of measles outbreaks is greater, according to the report. Door County has one of the highest vaccination rates for measles in the state, but Wisconsin has one of the lowest rates in the U.S.

The most recent immunization rate data is from June 2024, through the Wisconsin Immunization Registry. The U.S. has a 92.7 percent vaccination rate overall for measles/mumps/rubella or MMR and Wisconsin is second to last compared to other states at 81.4 percent among 24-month olds. Door County’s vaccination rate for measles is 85.9 percent.

Infants are at greater risk for getting measles, as children cannot be vaccinated until they are 12 months old. They are also more susceptible to serious illness and long-term health consequences, according to Reynolds. Pregnant women and immune-compromised people are also at higher risk for contraction and complications of the disease.

“As in most of medicine, prevention is always safer, cheaper and more effective than waiting for a disease to occur and then treating it,” Reynolds added. Treatment for a measles infection is supportive only, and there is no antibiotic against measles, as it is caused by a virus.

Preparation

For a disease like measles that has not been as prevalent as it was before widespread vaccination, healthcare providers may not be familiar with symptoms, or may have little real world experience with how cases present.

Door County Public Health is confirming vaccination status, specifically MMR, for anyone who comes to their office. It is also partnering with local medical providers to make sure they can identify measles, know proper isolation procedures and testing qualifications, according to Holly Neri, a public health nurse.

Other Wisconsin county health departments, including neighboring Brown County, said they are conducting “tabletop exercises” where medical staff run through different scenarios so they know exactly what to do in the event of a measles outbreak.

“Staff learned how to perform contact tracing and case investigation,” Katrina Nordyke said. “We also go over how to scale up those responses.” Nordyke is the deputy health officer for Brown County Public Health.

Brown County has been focused on measles for “well over a year now,” according to Nordyke, and they facilitate a regular meeting to look at numbers of cases, go through scenarios, and outline resources with other public health departments, schools and infection prevention personnel, she said.

Brown County also has a limited supply of MMR vaccines for adults in the event of an outbreak, and can share those with neighboring counties as it is a “hub” for vaccine distribution, Nordyke added.

“We revisited our internal preparation for mass vaccination clinics,” she said. “How do we utilize staff and resources? Hospitals would be a big part of that, and they work with their county public health departments.”

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services is also now testing for measles, as well as Covid and flu, as part of the Wisconsin Wastewater Monitoring Program, Nordyke reported. The program began as a way of testing for the virus that causes Covid. Samples of wastewater or sewage are tested to track levels of infectious diseases in an area, even if people do not have symptoms, or if cases are not getting reported.

Door County Public Health receives a state immunization grant annually, according to Neri. This year Public Health is directing it toward getting children turning two in 2025 up to date on vaccinations, especially MMR. Staff members also participate in weekly webinars to keep up with communicable disease updates and are equipped to do tabletop exercises like the ones conducted in Brown County, Neri said.

Public Health also routinely makes educational social media posts, encouraging people to get their MMR vaccine and explaining how to know if you are properly vaccinated with one dose or two. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, Reynolds encouraged people to find a board-certified doctor they trust to answer any questions or address concerns.

“There is misinformation in communities and on the Internet, which can be confusing and hard to sort out,” Reynolds said.

If an outbreak were to occur in Door County, Door County Medical Center and other local providers are mandated by state law to report measles to the local public health department, Neri said. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services publishes a guidance document for all providers.

Wisconsin Watch reporter Janelle Mella contributed to this report.