Locked Out: Door County’s affordable housing shortage

Door County Knock is reporting an in-depth series on Door County’s affordable housing shortage, addressing questions such as why the county lacks affordable housing, how market trends have contributed to its decreased availability and what roadblocks exist to building more. Click here to read more.

If there are questions you’d like the answers to or people you’d recommend we talk with as part of our reporting, please email us at [email protected].

Terms like “affordable,” “income-based” and “workforce” are used when it comes to types of housing needed in Door County. They are often used interchangeably and sometimes inaccurately. Words matter and indefinite definitions can lead to confusion for those seeking housing or trying to develop more of it.

Money–how much people make, how they make it and where they make it–is the basis of how housing needs are defined in this series about Door County’s housing shortage.

A shortage of housing, particularly affordable housing, is a nationwide issue with some general contributing factors. Income levels have not kept pace with a sharp rise in construction material and labor costs since the Covid pandemic. Home ownership is primarily impacted by this gap, while rent and income increases have largely kept pace with each other, according to a Wisconsin Policy Forum analysis in 2024.

In Wisconsin, median home prices increased by 53.3 percent from 2017 to 2022, while median income increased by only 19.7 percent. Median rent, including utilities, went up 21 percent in the same time period, and median income in renter households rose 22 percent. Median income refers to the number that falls in the middle of income values. Half of all incomes are above the median value and half are below.

Many renters who used to have high enough income to afford home ownership can no longer make that jump because home prices have risen sharply. Instead of moving out of the rental market into their own home, they continue to rent. This drives up the median income for renter households.

Demand outstripping supply is also a factor in the national housing shortage, as are restrictive zoning and land use policies in some areas.

Beyond these national factors, Door County has its own specific geographic and demographic influences that affect its housing needs. Geographically, the long, skinny peninsula means it costs more to get building supplies from urban centers like Green Bay to the farther reaches of the county, according to Mariah Goode. Goode was the county’s Land Use Services Department director for decades and is involved in several housing-related organizations in Door County.

The additional expense of transporting supplies and finding labor on the peninsula is not new, but it exacerbates the recent surges in building costs overall.

Lack of infrastructure in Door County is another factor, and a very expensive one for housing developers, Goode added. Only Sturgeon Bay and Sister Bay have municipal water systems. Every other community relies on private wells and septic systems.

State and local requirements also affect prices. For instance, Wisconsin building code requires sprinkler systems in commercial buildings with more than 20 residential units or two or more stories high.

These developments need a sprinkler system with a heated cistern or sewer and water hookup. Either option can contribute upwards of $70,000 to a project, according to Goode. Circumventing this requirement by building a one-story multi-family project with fewer than 20 units means more land costs, she added.

Municipal and county zoning restrictions, a seasonal swell in economy and population, a higher percentage of aging people and a high number of vacation or second-home buyers are also contributing factors to the local housing landscape and are taken into consideration when defining housing terms in this series.

The crux of Door County’s housing shortage lies in its lower incomes. In areas with higher median incomes, like Madison or even Green Bay, developers and landlords can charge more for rent.

“People in Door County don’t make enough money to rent or buy at (the prices) developers need to make money,” Goode said.

Affordable

Many developments are marketed as “affordable housing,” and the term is often used interchangeably with other terms like “low income,” “attainable” and “workforce” housing, according to Stephanie Servia, planner and zoning administrator for the City of Sturgeon Bay.

A question often posed is, “affordable for whom?” Throughout this housing series, Knock will use the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of affordable.

Area Median Income or AMI, a number calculated by HUD, defines what makes housing affordable. AMI is the midpoint of an area’s income levels, with half of the families earning less than that number, and half earning more. AMI is the key determining factor for most housing program eligibility.

Door County’s AMI for 2025 is $103,700, according to HUD. Regions with large urban areas typically have a higher AMI than rural areas. HUD combines Brown and Kewaunee county AMIs at $110,500. Dane County has an AMI of $129,800. Bayfield County, which has half the population of Door County but has a similar rural character and tourism-based economy, has an AMI of $90,700.

HUD uses a formula to determine income limits for affordable housing based on the AMI. The formula also takes into account family size. For Door County in 2025, the income limits based on 80 percent of the area median income are $56,500 for one person or $64,550 for two people, for example.

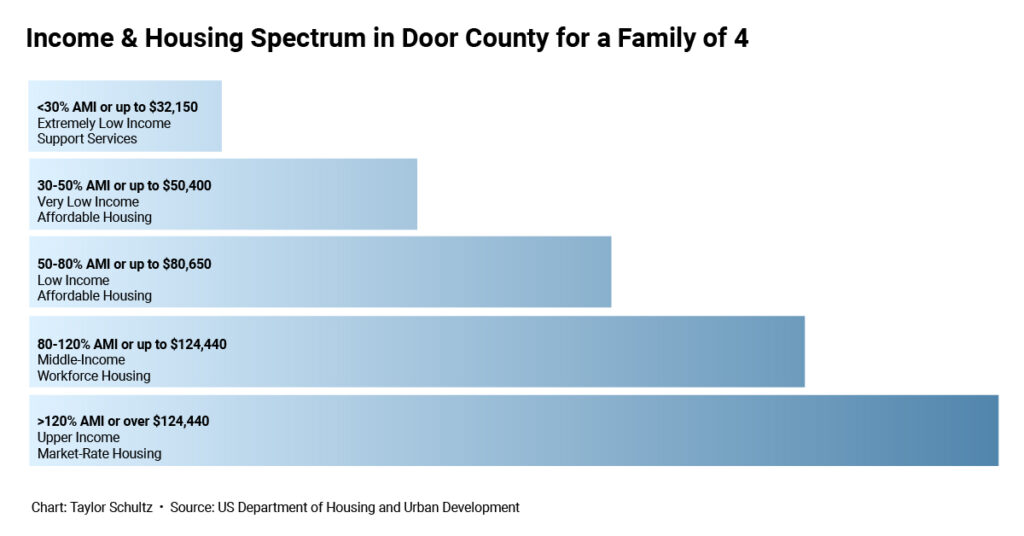

The most basic definition of “affordable” housing is housing that costs less than or equal to 30 percent of a household’s gross income. For income-limited programs, HUD defines families making 80 percent of the AMI as “low income,” households making 50 percent of AMI as “very low income,” and those making 30 percent of AMI “extremely low income.”

A family of four in Door County, making 80 percent of the AMI, has an annual income of $80,650.

The Door County Economic Development Corporation commissioned a housing study in 2019 that determined an affordable home in Door County would cost between $60,000 and $124,000. A general guideline for homeownership affordability is the home should cost no more than twice the household’s annual income. A family of four making 80 percent of the AMI would theoretically be able to afford a home that costs about $160,000.

The average home price in Door County in 2025 is $424,076, according to Zillow.

Income-assisted

Income-assisted housing is also referred to as subsidized housing or used interchangeably with affordable housing. It refers to housing that is reduced in cost for low-income households. According to HUD’s definition of low income, In Door County, a family of four is considered low-income if they make about $80,000 or less per year.

Most income assistance housing programs in Door County target households in the “very low” or “extremely low” income range of HUD’s definitions. For a local family of four, that is $50,000 or less per year, according to Sue Binish. Binish is the executive director of the Door County Housing Authority.

Some developments provide income assistance for some or all of their units. On the flip side is what DCHA does.

DCHA provides rental assistance to households that qualify for the Housing Choice Voucher Program called Section 8. HUD oversees the program and provides funding, and local housing authorities administer it.

The voucher program is different from public housing, Binish said, an important distinction because people often confuse the two. Public housing is federally funded and owned and managed by local housing authorities. DCHA does not own or manage any property.

“Our system is connected to the tenant,” Binish explained. “With public housing or low-income properties with rental assistance, that assistance stays with the apartment.”

Once a voucher applicant is approved, they have four months to find a landlord that will accept the program and is within the housing authority’s payment standards. Payment standards are the most the housing authority will pay toward rent and utilities and are based on fair market rents, unit size, utility costs and other factors, according to Binish. Tenants usually pay 30 percent of their monthly income toward rent, and the DCHA pays the remaining amount up to the payment standard.

Recipients can also use vouchers to rent an apartment that is income-restricted and/or subsidized, as long as the landlord accepts vouchers.

The housing authority receives a set amount of funds to be used toward vouchers every year, and that amount is set by HUD, taking into account the need from the previous year, Binish explained. DCHA paid out $883,853 in rental assistance in 2024. It also administered an additional $45,999 for a supportive housing program for veterans that HUD partners with the Department of Veterans Affairs to fund.

Door County has about a six-month waiting list for vouchers, Binish said, and the only demographic categories that are prioritized on DCHA lists are “resident” versus “non-resident.” Every housing authority is different, she said, and some of them have several preferences aiming to assist those with the greatest need, such as disabled, elderly or homeless individuals. More than half of DCHA applicants are elderly and disabled, she said.

The demand for voucher assistance is trending downward over the past several years, Binish said. DCHA used to get 30 applicants a month or more, she said, and now it is closer to 10 per month.

“I could not tell you why that is,” she added, but it could have something to do with housing scarcity.

Receiving a voucher is not a “magical thing” that guarantees housing, and some vouchers are unsuccessful, Binish said. Applicants unable to find housing within the four-month time limit have to reapply and get back on the waiting list.

“It’s hard to find units that work with our payment standards because the cost of housing is getting to be more and more,” she said. Vacancies often are filled without being posted publicly, and open units fill up as fast as word travels.

“We have a lot of great landlords willing to work with us,” Binish said. Many landlords appreciate voucher tenants, she added, because the portion DCHA pays goes directly to the landlord and is guaranteed income.

There is no time limit for how long one can receive their voucher, she said, and once someone is on the program, they can stay on it as long as they need, with regular income verifications by DCHA. One local resident has been receiving voucher assistance for 36 years, she added, because they are disabled and will never have the opportunity to increase their income.

“We encourage working (your way) off the program,” Binish said, but for single working parents or households with one income, it is a safety net.

There are no income-assisted housing ownership programs administered by DCHA, Binish said. Owning a home is out of reach for most of its applicants, especially with the high home costs in Door County, she added.

People on the outside think people using vouchers and other income-assisted housing programs are “just living off the system,” Binish said. “That is so not true. These are hardworking people, parents working 40 hours a week, elderly people working into their mid-70s.”

“Living off the system, sitting home and doing nothing? That doesn’t exist,” she said.