Jeremy Desing tested negative, but the coronavirus has hit him hard nonetheless.

After a work trip to Milwaukee in early March, Desing felt sick, with all the symptoms of the flu except a fever. When his symptoms didn’t improve after 10 days in self-quarantine, he went to the Door County Medical Center.

“They put me in the ICU,” Desing said. “Everybody that ever came into my room was all gowned up.”

Tests for coronavirus and influenza A and B came back clear, and Desing was diagnosed with an infection. But when he returned home after a few days, he faced unemployment.

Desing, 45, is the executive chef of the Chef’s Hat restaurant in Ephraim. The restaurant typically is closed in March and April, Desing said, so he wouldn’t usually have income from his main job right now. But he ordinarily would pick up a second job during the closure, and he’s been unable to do so this year because of the pandemic.

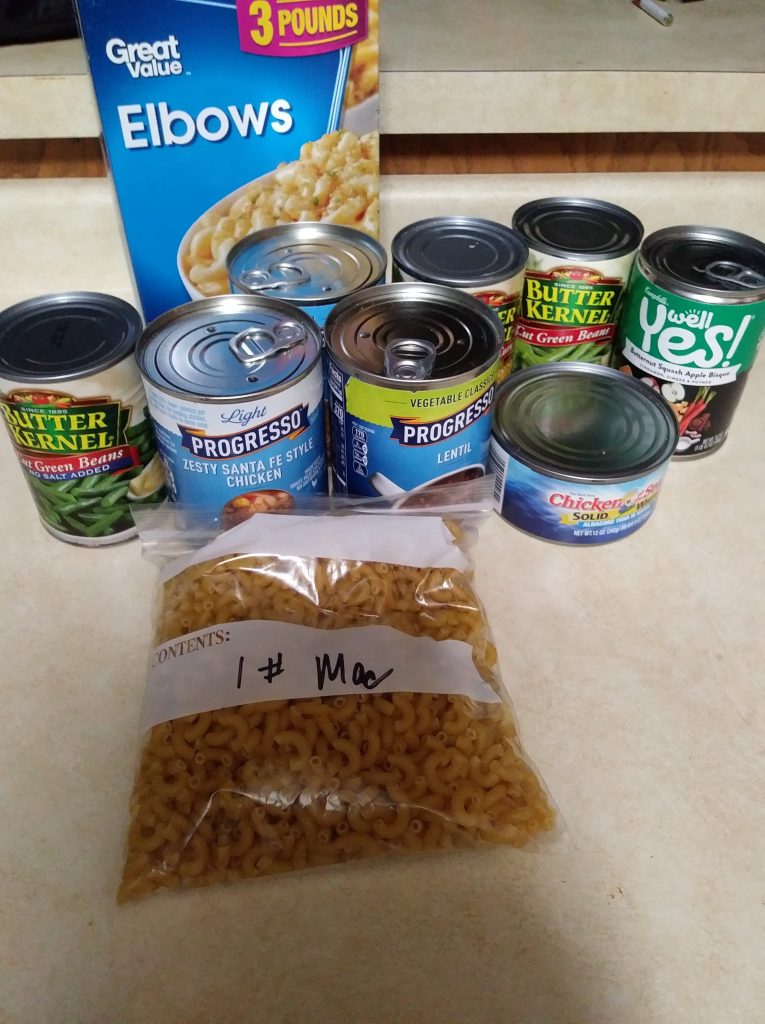

Without any income, Desing said, he had to cancel his cell phone service and has been getting groceries from a food pantry every week – limiting himself to a few staple items such as cereal, soup, pasta and pasta sauce.

“I’ve lived poor my whole life, so I’m pretty good at it,” Desing said. “For me, it’s just the sitting at home all day that sucks. Last night, I had baked beans with hot dogs cut up into it for dinner, and then (had) the rest of it for lunch.”

Desing is not alone. About one in three households in Door County – more than 4,100 households in total – earned less than the county’s basic cost of living in 2016, according to a United Way report. That included 10 percent of households (about 1,300) that earned less than the federal poverty level, and an additional 22 percent (more than 2,800) that fell under a category United Way describes as “asset limited, income constrained, employed” (ALICE) – households that earn more than the federal poverty level, but still not enough to cover expenses such as housing, food, childcare, health care and transportation.

Those households – many of the county’s workers, families and seniors – are among the most at risk of long-term economic harm from the coronavirus pandemic. Even if social distancing restrictions are lifted and businesses reopen relatively quickly, local service group leaders say, these residents could continue to struggle well into the summer.

“I’ve lived poor my whole life, so I’m pretty good at it.”

Jeremy Desing

“We already have a fairly significant population of low to moderate income families,” said Brian Stezenski-Williams, the CEO of the Boys and Girls Club of Door County. “There’s a huge number of folks who are right at the edge of just enough resources – and often not even at the edge (before the pandemic started).”

“All of a sudden, everything stops cold, and you have very limited options,” he added. “And not a lot of margin for error.”

Assistance programs are in place to help, including a United Way emergency response fund and the Door County Meals Cooperative food program, which is providing 650 dinners per week. But the current version of the meals program will end in June when some of the organizations running it shift to providing lunches for children over the summer, leaving the continued availability of food for the residents who use the service somewhat in question.

Life without income

For Desing, unemployment has brought other problems.

Being without cell phone service hasn’t been too bad, he said, because he still has internet access and can keep in touch with friends via Facebook. Most of the calls he got when he had service, he said, were from telemarketers.

But the food pantry he goes to requires calling in advance, Desing said, and he at one point resorted to going with someone else and calling from outside the door.

There’s also the matter of his hospital bill. Desing has no health insurance, so he’s faced with the possibility of paying for his stay out of pocket. He hasn’t actually received the bill yet, he said, but he got a letter in the mail from the Medical Center with an application for financial assistance, which he hopes to get.

Staying at home without work also means boredom. Every day involves three activities, Desing said: cleaning the house, gardening (when the weather allows) and watching TV.

“You can only clean so much, and you can only watch so much TV,” Desing said.

In a typical year, Desing shares the house he lives in – which is owned by Chef’s Hat owner Todd Bennett – with up to 12 other employees during the summer. Desing started the garden, he said, in part to liven the place up.

“I always grow veggies – basil, mint, tomatoes, jalapeños – all summer long,” he said. “It makes the deck look nice. Everybody likes it when they come out here.”

Desing said he’s tried to volunteer his time. On Easter, he said, when Chef’s Hat offered free meals, he “came in that morning and basically served breakfast until like 12 o’clock in the afternoon.”

Assistance programs available

United Way of Door County and the Meals Cooperative, which includes United Way, the Boys and Girls Club and several other organizations, have launched assistance efforts in the weeks since the pandemic began.

United Way, partnering with the Door County Community Foundation, activated an emergency response fund in March that has raised more than $400,000 as of April 22, according to the community foundation’s website.

The two groups are meeting weekly to review applications for funds jointly, with most money going to agencies that serve vulnerable populations in the county, said Amy Kohnle, the executive director of United Way of Door County. The groups have awarded more than $122,000 in grants so far. Wednesday will be their fifth week of reviewing applications.

Recipients so far have included the Door County Medical Center, the Boys and Girls Club, the Meals Cooperative and Scandia Village.

Kohnle said the groups have discussed using the fund for both short- and long-term needs but decided to focus on initial and emergency needs for now. The fund will continue to be important in the long term, she said.

“The population that’s getting fed is much broader. That puts challenges on us to find funding for all the adults we’re feeding.”

Brian Stezenski-Williams, CEO of the Boys and Girls Club of Door County

“Once the county reopens, for lack of a better term, how it reopens will kind of determine our next steps for that relief fund,” Kohnle said. “Do we change our strategy? What other ways can we assist our community through an economic recovery?”

At the Boys and Girls Club, which has been among the leaders of the operations of the Meals Cooperative, Stezenski-Williams said the effort is providing 650 meals per day, each of which includes dinner and a snack. Meals are offered Monday through Friday at pickup locations ranging from Algoma to Fish Creek.

The Meals Cooperative is based on a summer meals program that the Boys and Girls Club and the YMCA put on for children, Stezenski-Williams said. That program typically distributes 700 lunches per day to 14 drop-off sites, he said.

Stezenski-Williams said he believes the cooperative will be able to get reimbursements from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction for meals provided to children. Those two agencies typically provide a major funding source for the summer lunch program.

But the current meals effort is serving all ages, with more than 50 percent of the recipients adults, Stezenski-Williams said.

“The population that’s getting fed is much broader,” he said. “That puts challenges on us to find funding for all the adults we’re feeding.”

The cooperative has received some private funding, as well as a grant from the United Way emergency response fund, Stezenski-Williams said. The group also has applied for a grant from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine.

Staying afloat

Desing said he had not heard about the Meals Cooperative, but he’s grateful for the efforts of the county’s food pantries.

In addition to food from the pantry, he said, he received financial assistance from the Ephraim Moravian Church. (Disclosure: Ephraim Moravian Church pastor Dawn Volpe is a Knock board member.)

Desing said he’s filed for unemployment but doesn’t anticipate receiving any money for a few weeks because when he filed for unemployment two or three years ago, he was audited multiple times and was charged for the cost of the audits when the auditors didn’t like one of his job searches. Those costs are now being garnished from his unemployment checks, he said. (The Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development did not respond to a request for comment by publication time.)

Even when he does start to receive unemployment, Desing said, he won’t get the full amount because he’s behind on child support payments, and unemployment checks, just like his paychecks, are garnished. That also means he won’t get a CARES Act stimulus check or a tax refund, he said.

Desing said he’s fortunate that Bennett is both his boss and his landlord, because he understands that Desing doesn’t have any income coming in.

Bennett said he’s applied for the Paycheck Protection Program, and if he receives a grant or loan, he probably would open Chef’s Hat for carryout and pickup orders and put his employees back to work.

Right now, though, Bennett said there’s not enough business in Door County to justify opening his doors. He said he is struggling, too – he’s had to file for unemployment for the first time in his life.

With the assistance he’s gotten, Desing said, he’s OK for now.

“I got a fridge of food, I got a van full of gas, and I got 50 bucks left in the bank,” he said. “I’m doing pretty good.”

Uncertainty clouds future

The future is less sure. Desing said he hopes that after Gov. Tony Evers’s current stay-at-home order expires on May 26, the Chef’s Hat will reopen June 1.

He’s concerned that if social distancing and other preventative measures still are required, though, opening might not be feasible. The restaurant would have to provide individual salt and pepper packets on each plate to replace shakers, and condiments on the table would not be allowed, he said.

Desing said he’s concerned about how long the pandemic will last.

“I actually moved up here (in December 2018) to make more money,” he said. “And now, it’s like I’m back to where I was back in Green Bay, not making any more money.”

“If it goes into June, I will be struggling very much,” he added. “If it goes past May and into June, this will be hurting me. Financially, I won’t be able to afford anything – I won’t even be able to afford to put gas in a car to get myself to a new job if I get one.”

“If it goes past May and into June, this will be hurting me. Financially, I won’t be able to afford anything.”

Jeremy Desing

Uncertainty also makes planning assistance efforts more difficult, Kohnle and Stezenski-Williams said.

The Meals Cooperative program is “rock solid” for the next month, Stezenski-Williams said. In June, though, the Boys and Girls Club and the YMCA will shift to their usual summer lunch program for children. The lunch program fills a need during the summer, when schools that now are providing children with breakfast and/or lunch stop doing so.

The Boys and Girls Club concluded that its kitchen does not have the capacity to produce more than the 700 meals per day it does for that program, Stezenski-Williams said.

“That leaves the question of who’s going to fill the void for the evening meal,” Stezenski-Williams said, a discussion that the Meals Cooperative organizations will begin Tuesday.

“There’s still clearly a lot of adults who need food,” Stezenski-Williams said. “The question is, is there another kitchen who can do that? Or is it best to maybe direct the food to the food pantries and let them distribute?”

The lack of clarity about the summer season can worsen anxiety about the pandemic, Desing said.

“A chef doesn’t like to feel like he’s not ready,” Desing said. “That’s the whole idea of the term ‘prep’ – they want to make sure they’re ready. They want to make sure they’ve got their ‘mise en place’ (everything in its place). They want to make sure they’ve got their towels folded.

“If the chef doesn’t feel like they’re ready, then anxiety will take over. And then they start yelling at people, and it’s just not a good thing.”