This story is part of a series on opioid and methamphetamine addiction in Door County.

“No buh-byes?” said the little voice.

“No sweetie, you aren’t going buh-bye,” Jennifer Singer told her daughter Isla. The three-year-old had asked her mother that question so many times, Singer had lost count. July 16 of this year was the first day Isla was with her mother full-time for a “trial reunification” after a year spent in foster care.

It was a year characterized by Singer receiving treatment for opioid addiction, participating in Door County’s drug treatment court program, and meeting county child protective services’ requirements to get Isla back.

Like virtually every community in America, Door County has residents who are suffering from substance use disorder. CPS cases involving illegal drugs are on the rise, as are foster placements, according to a Knock report last year. Substances like fentanyl and methamphetamine are circulating here, making it absolutely a local problem, according to authorities.

In 1987 the American Medical Association classified addiction as a disease, a chronic medical condition defined by the inability to control use of a substance or substances despite negative consequences. Genetics, mental illness, chronic stress, and trauma are some of the factors that can contribute to addiction, according to the association.

But authorities need to take care not to single out one cause, said Circuit Court Judge David Weber, who leads the county’s drug treatment court program, a treatment-based alternative to jail.

“It’s a human problem. It’s different with everyone,” he said. Rather than focusing on causes of substance use disorder, Weber said the treatment court program is focused on helping people recover from the disease.

Relapse is part of the process of treating addiction, according to the drug treatment court therapist Lisa Barnaby. Relapse rates are between 40 and 60 percent—on par with other chronic disease relapse rates—according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Barnaby said it could take years before someone is on a solid foundation of long-term recovery.

Door County’s drug treatment court and diversion programs aim to build that foundation. Law enforcement, the county Health and Human Services department and providers try to find alternatives to punitive approaches to addiction.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, but the potency of opioids like fentanyl, the long-term physiological consequences of meth, and a rise in polysubstance use make the stakes very high for getting people the help they need, said Singer, who has lived in Sturgeon Bay for the last decade.

Gaps in services, staffing shortages, and persistent stigma around people dealing with addiction complicate the problem in Door County right now.

Getting personal

In 2021, 46.3 million people nationwide aged 12 or older reported having a substance use disorder, according to a study released in January 2023 by the U.S. government. This does not take into account the millions of other people affected by the condition: family, friends, colleagues and neighbors. Often people working in the treatment and recovery field have firsthand experience with addiction in their personal lives.

Both of Weber’s daughters struggled with addiction. His oldest daughter died two years ago as a result of the disease. He and his wife are straightforward when they talk to people about how substance use disorder has impacted their family. Weber said he thinks there is community support for the disease that did not exist 40 or 50 years ago. Addiction is not a moral failing, he added.

His own family’s struggles led Weber to be intrigued by the treatment court model when he was shadowing a judge in Outagamie County, and he helped spearhead Door County’s version, launched in 2020.

“I put my heart and soul into this,” Weber said.

“As long as they’re in this office and in this building, then they’re not using. And they’re safe.”

Door County drug treatment court therapist Lisa Barnaby

Barnaby also has first-hand experience watching a loved one with substance use disorder. Her husband died of a drug overdose. At first she wanted nothing to do with addiction, she said, but as she shared her story, people encouraged her to pursue a career in treatment. She had an internship at a jail, where her first client was a young intravenous heroin user.

“Something just clicked into place in my head,” Barnaby said. “We’ve got to do something.” She is now the Alcohol and Other Drug therapist on the county’s treatment court team.

“I’ll probably die in this chair,” she deadpanned from her office. She credits her co-workers at HHS, and her own compassion for people suffering from addiction, for keeping her motivated in a job with very high burnout rates.

“I will see a client every hour, on the hour, on the hour,” she said. “It’s a touch point. As long as they’re in this office and in this building, then they’re not using. And they’re safe.”

Magnitude

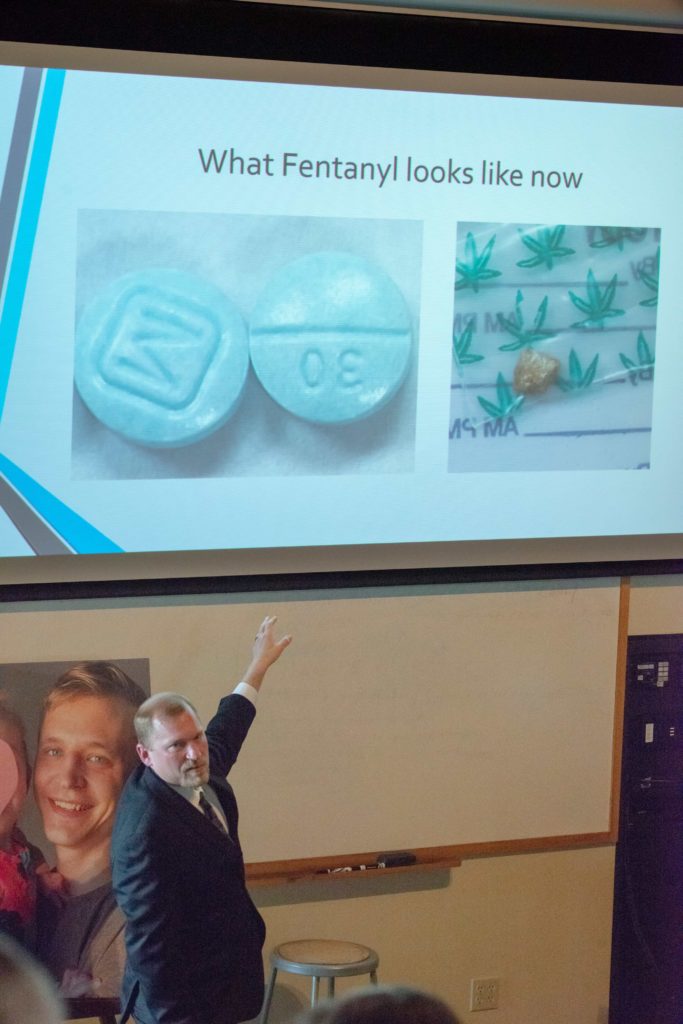

According to a report from the Door County Sheriff’s Office, out of 222 drug cases from January 2020 to July 12, 2023, 46 involved meth and 27 involved opioids. The first case involving fentanyl that the Sheriff’s Office encountered in the county was in March 2021.

Fentanyl has comprised 21 out of 27 of opioid cases since then, and 32 of 64 longer-term drug investigations involve meth as the most common substance found by law enforcement.

Jonathan Gilson was the drug investigator at the Sheriff’s Office for eight years. If it weren’t for drugs, crime rates would be much lower, he said, adding that they are at least on the periphery of most criminal behavior.

Weber agreed, and said stealing to support substance use is often the case with property crimes in his courtroom.

But big drug busts are not that prevalent in the county, said current drug investigator Elizabeth Williams. Williams has been with the Sheriff’s Office for two years and said most drug users travel to Green Bay or farther to purchase what they need for personal use. A large-scale meth lab or drug-dealing operation would stand out in such a small community, she added, making it too risky for the size of the market.

Many people with substance use disorder do not come into contact with Williams and her law enforcement colleagues, but they still need help. For those on the treatment side of things, the number of clients seeking services feels like a broken dam, according to HHS behavioral health manager Donna Altepeter.

Altepeter is doing all of her office’s incoming client screening right now in addition to her regular responsibilities, she said. A case manager position has been open for six months.

For those on the treatment side of things, the number of clients seeking services feels like a broken dam.

Door County HHS behavioral health manager Donna Altepeter

HHS receives federal funding and is mandated to give priority for treatment to pregnant women and intravenous drug users, Altepeter said, leading to a triage system where it might take longer for some clients to get seen. Meanwhile, co-occurring disorder therapists like Barnaby—who are trained to treat mental health issues and substance use disorder—are in short supply.

The county has tried to expand options over the years that are not specific to AOD counseling, HHS director Joe Krebsbach said, focusing instead on Comprehensive Community Services, a program that provides mental health and substance use disorder case management and adds resources like peer counseling and recovery coaches.

“We’re still working on that,” he said. “We developed (the treatment court program). But we haven’t added to the number of counselors. So that is still an interesting problem.”

Segregation of care contributes to stigma

Timmie Sinclair, the community impact coordinator for United Way of Door County, said substance use disorder is the only medical condition that is persistently stigmatized and criminalized.

“We decided how we’re going to deal with that,” she said of cultural attitudes around addiction. “We’re going to come up with these really horrible, bewildering, draconian, inhumane ways of treating the narcotic addict.” People who are struggling with addiction are strictly supervised and must go to a special clinic, separate from other medical facilities, to receive methadone—a medication that reduces opioid craving and withdrawal symptoms—and other forms of addiction medication, according to Sinclair.

One medical condition is being segregated from the rest, she said, and “we decided that addiction was a problem for the legal system and not the medical system.”

“We decided that addiction was a problem for the legal system and not the medical system.”

United Way of Door County community impact coordinator Timmie Sinclair, on the shifting societal approach to addiction

Sinclair is exasperated by an approach to substance use disorder she said is “absolutely bonkers.” If a patient is being treated with methadone, there is no way for their primary care doctor to know unless the patient tells them or gives express permission for someone else to tell them, she said.

She gave the example of a heart attack patient who is on methadone. There would be no way for emergency room staff to know that was the case, unless the patient tells them, which can’t happen if they are unconscious. Drug interactions and other treatment choices are affected.

“Can you imagine if we treated cancer this way?” she added.

In the void left by the shift away from medical treatment, an addiction care industry of inpatient and outpatient treatment has cropped up. Many treatment options are based on 12-step programs and are great, Sinclair said, but they aren’t regulated or credentialed, and they aren’t medical.

Singer has relapsed from substance use disorder more than a dozen times, and has a lot of experience with both inpatient and outpatient addiction care. Treatment providers have power over a vulnerable population and have little oversight, she said, and it is a situation that is ripe for abuse.

Stigma-driven barriers and pressure

The Sturgeon Bay recovery community is tiny, Singer said. She leads a fellowship-based support group at The 115 Club, a community organization dedicated to improving the lives of those involved in any 12-step recovery program, according to its Facebook page. (Disclosure: Knock board member Peter Mannoja is The 115 Club’s president.)

Singer blames the stigma around addiction for low participation in recovery programs like hers. She said there are people who won’t walk into The 115 Club because everyone in town knows why you go there.

Sinclair, the United Way coordinator, said stigma comes from the longtime criminalization, rather than medicalization, of addiction.

“The illness of addiction, if somebody has that particular illness it is like we’re given carte blanche to absolutely undervalue their life,” she said.

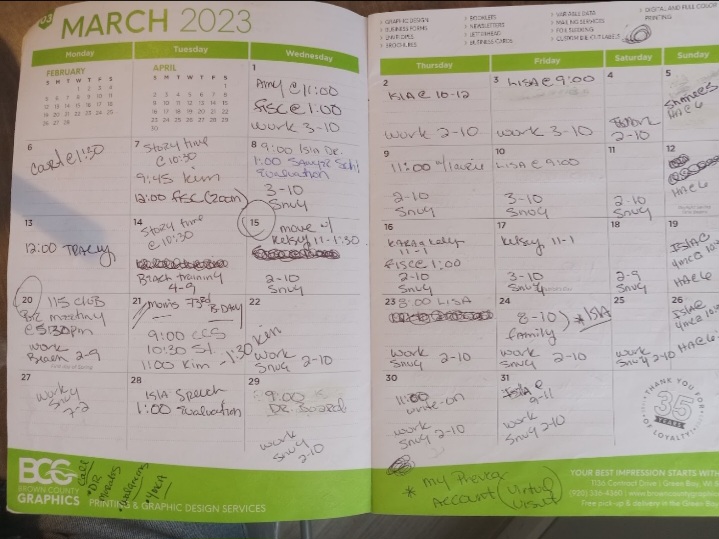

Since Singer began participation in the treatment court program last year, her schedule is full. Work, therapy, court dates, drug screenings, financial counseling, and until recently, scheduled visitations with Isla filled her calendar.

Now, in addition, she is a full-time single parent. Isla attends daycare that CPS helps pay for, which Singer is grateful for as she could not afford it on her own. It is one of many worries that crowd her mind.

On July 15, with Isla in her carseat after she picked her up from foster care for the last time, Singer sat in the driver’s seat and cried. She was so happy to have her daughter back, but felt the new and suffocating pressure of ongoing CPS involvement, she said.

If anyone makes a report to CPS during the trial reunification period, CPS can mount an investigation, and Isla could be taken away again, according to Singer. When Isla has a temper tantrum or other “normal three-year old stuff,” Singer gets so anxious she sweats through her shirt.

She is always trying to stay ten steps ahead of the next meltdown. “I think, ‘What am I going to say if this ends up with police or social workers at my door?’” she said.

Singer and Isla are getting support from a family therapist through the treatment court program, who is helping them navigate this transition. Recovery is hard enough in a perfect world where you can focus solely on recovery, Singer said, but the extra layer that parents with CPS involvement experience makes it that much harder.

Things like housing, employment, and financial security add more difficulty. Often those with substance use disorder have burned a lot of bridges, said Barnaby, the HHS therapist, and they come for services with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Nobody wants to rent to them or hire them because of a criminal background, she added. “So here we are, trying to get them to reintegrate into the community, care about your community, but your community is turning their back on you,” Barnaby said.

Besides the local affordable housing shortage that has been making headlines for years, there is a dearth of sober housing in Door County. Kimberley House, a privately run sober living home in Sturgeon Bay, closed in July 2015 due to lack of funding, according to former house manager Paul Schuster.

NEW Door Sober Living, run by Eli Phillips and his partner Angie Levens, operates in Sturgeon Bay, and according to its Facebook page, “is a safe environment for someone to start or continue their road to recovery.”

Though the County Board of Supervisors discussed plans for a sober living facility last year, those plans haven’t yet come to fruition.

There are also no inpatient facilities for youth treatment that take Medicaid in the entire state, according to HHS’s Altepeter. That is a huge gap in services, she said.

A changing legal landscape

On July 31, the Sheriff’s Office responded to a drug overdose call at a home in Sturgeon Bay, where a 42-year-old male resident was revived with Narcan, a medication to reverse opioid overdoses. The call led to investigators securing a search warrant for the residence and taking four women into custody for drug possession, trafficking and outstanding warrants. Task force members also seized 16 fentanyl pills at the scene.

Williams, the Sheriff’s Office drug investigator, said it’s always good when law enforcement can find evidence and make arrests as the result of an overdose.

United Way’s Sinclair said she’s concerned that fear of arrest could lead to more fatal overdoses. Wisconsin’s Good Samaritan laws were sunset in 2020 and have not been reinstated. The original legislation was enacted in 2013, and the intent was to provide limited criminal immunity to witnesses of overdoses who seek help.

Now, if one drug user is overdosing and another drug user calls 911, both could possibly have issues with police, said Sinclair, creating a potentially dangerous situation where people might not get help for fear of prosecution.

Narcan is free from HHS, and in order to expand access to it, NEW Door’s Philips and Levens purchased a used vending machine, stocked it with Narcan and fentanyl test strips, and put it outside their property on 14th Avenue in Sturgeon Bay. Since the machine’s installation in mid-July, it has been vandalized and is awaiting repair, according to a sign posted on the machine.

For now, people will continue to use chemicals to alter their moods and perceptions, Sinclair said, and the community needs to be realistic in its approach to drug use. Education and access to resources are crucial to prepare people for what to expect and how to handle it when “things go sideways,” she said.

To contact Door County Health and Human Services about mental health or addiction services, call 920-746-7155 during business hours.