In June 2024, torrential rains in Sturgeon Bay flooded the area around 14th Ave., and caused about $45,000 worth of damage to the Habitat for Humanity ReStore. It was not the first time the city has faced flooding issues in recent years. Sturgeon Bay’s unique geology and in some cases, outdated stormwater infrastructure, pose challenges that the city is trying to address.

With the population nearing 10,000, the Sturgeon Bay city council is taking a “proactive measure” and forming a stormwater utility in advance of increased state regulation of stormwater management and to better tackle the city’s flooding issues, according to City Administrator Josh VanLieshout.

The utility has a targeted implementation date of 2026 and the city has a lot of questions to answer in the meantime.

In November 2024, the city’s Finance/Purchasing and Building Committee recommended hiring Cedar Corporation, a design and engineering firm based in Green Bay, to design and implement the stormwater utility for a contracted fee of $46,250. The city council approved the recommendation, and Cedar Corporation’s Mike Kaster and Robert Jones, lead engineers for the project, held a public information meeting on April 22 in conjunction with the city administrator.

The population of Sturgeon Bay was 9,657 when the 2020 census was taken, and the census bureau estimated it was at 9,861 in 2023. “It might already be at 10,000,” VanLieshout said in a phone conversation about the proposed utility. Whether or not that is the case, the city’s population is sure to be there by the time the next census is taken in 2030.

Cities in Wisconsin are arranged into four classes based on population. Once the federal census records a population of 10,000 residents, Sturgeon Bay could go from being a fourth class city to a third class one. In order to do so, the city’s mayor must make a proclamation declaring the change. Changing a city’s class designation is not mandated by state law.

However, some regulations are mandated by the state based solely on population size. One of them is that once Sturgeon Bay reaches 10,000 people, the city will need to apply for a Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System, or MS4 permit through the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

More than 200 Wisconsin municipalities are required to have MS4 permits under Wisconsin law. Though not required by law, many of those cities, towns and villages have formed stormwater utilities to fund and manage the infrastructure and mitigation costs incurred by permit regulations.

When rain or snowmelt encounters impervious surfaces like roads, rooftops and parking lots, it runs off into area waterways, rather than getting absorbed into the ground. Along the way, runoff picks up sediment, trash, chemicals, road salt and other harmful pollutants and carries them into those waterways.

Only three cities in Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Madison and Superior, treat stormwater through their wastewater management systems. Most often, stormwater flows through storm sewers directly into waterways. According to the EPA and the DNR, stormwater runoff is the most significant source of water pollution to urban waterways.

How—and why—to create a utility

“This is certainly not cutting edge,” VanLieshout said, indicating that public stormwater management has been going on since the 1990s, and stormwater utilities became even more common after the Environmental Protection Agency stepped up stormwater regulation requirements under the Clean Water Act in 2005.

MS4 permit requirements include increased public education and outreach, public involvement and participation, illicit discharge detection and elimination, construction site pollution and runoff control and post-construction stormwater management, as well as identifying and mitigating areas of concern and impaired waterways.

The City of Sturgeon Bay already manages stormwater systems and activities like street sweeping and maintaining culverts, ditches, pipes and retention ponds. These services are paid for through general fund taxes, and establishing a stormwater utility would shift funding of these services to a more stable model, Cedar Corp engineers explained during the April presentation.

The city has seen an increase in road flooding in multiple areas over the last several years, according to Alderman J. Spencer Gustafson, who represents District 4 in Sturgeon Bay. A dedicated stormwater utility would be able to set aside funds for projects and work to address these issues, he added, rather than reacting to them as they happen.

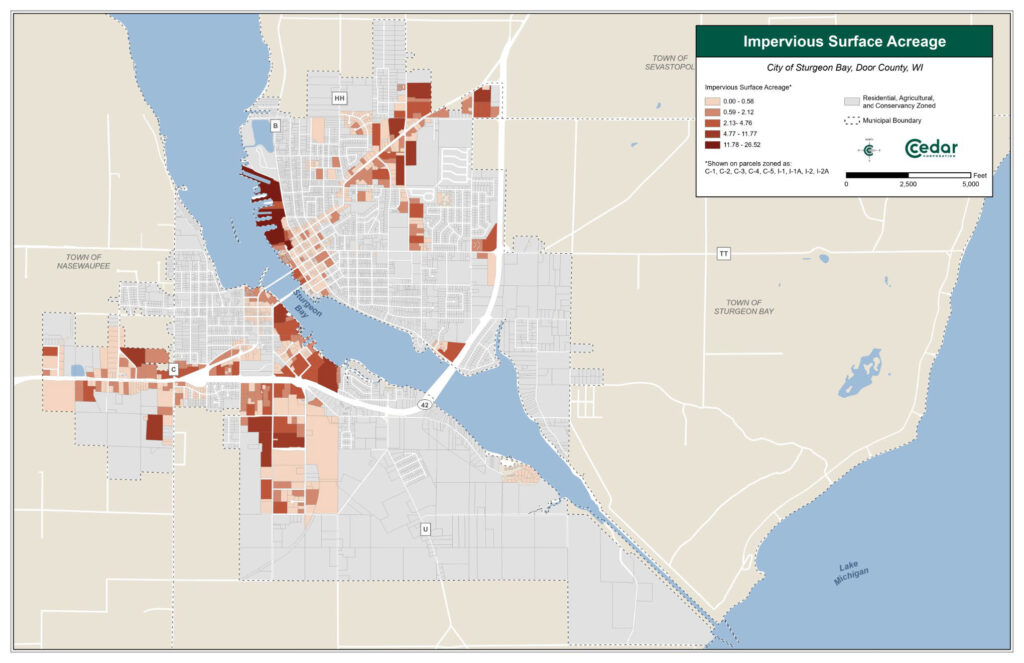

Bringing more equity and fairness in how stormwater management is funded is another component of the utility, according to city representatives. Currently residential property owners are shouldering 74 percent of the general fund tax burden compared to commercial properties at 20 percent.

Single-family residences have an impervious surface area that is 20 to 33 percent of their total property area versus commercial, industrial and multi-unit residential developments with impervious surface areas making up 56 to 93 percent of the total area.

A stormwater utility would bring the cost burden more in line with what kinds of properties are actually contributing the most to stormwater runoff, with 58 percent of the share of stormwater utility fees being paid by commercial, industrial and multi-unit residential developments, and single family residences contributing 26 percent of those fees.

“Right now, all taxpayers are footing the bill for stormwater projects, regardless of how much runoff their property actually generates,” Gustafson said.

For taxpayers wondering if a stormwater utility fee translates into less property taxes, it’s not a “one for one” situation, such as if a homeowner pays $200 per year in utility fees, then the same amount will be deducted from their taxes, VanLieshout said. However, services being paid for by those taxes currently, like street sweeping and cleaning of catch basins, will be moved to the utility and out of the general fund, he said.

Under levy limit laws, in order for a municipality to create a utility, it must reduce the levy by the corresponding amount. Whether that reduction will result in tax cuts, flatter tax rates or having more money available for other desirable services is to be determined, according to Kaster.

A utility is flexible in what it can fund as well. Kaster gave an example of how high water levels affect stormwater drainage and shoreline erosion, things that coastal landowners are responsible for, but if Sturgeon Bay had a stormwater utility it could potentially develop an assistance program for those property owners.

A less obvious or visible issue than flooding and erosion, in regards to stormwater, is the quality of stormwater discharged into the bay of Sturgeon Bay, VanLieshout said. Boating, fishing, beach-going and just enjoying the aesthetic quality of Sturgeon Bay’s public waterfront can all be sustained by improving overall water quality, he said.

An MS4 permit requires meeting certain water discharge quality standards, and the city will have to figure out exactly what it is discharging with its stormwater and how to demonstrate water quality improvements.

Part of crafting policy for a stormwater utility also means analyzing what the city has been spending on stormwater management the last few years, what the city wants to spend, save, and fund, and how to react to changing environmental conditions and natural disasters, according to Kaster.

“The goal is to keep rates predictable, get them to where people can depend on them and they don’t vary wildly,” Kaster said. “You want to set it up where there are no surprises.”

Balance sought

The city has more work to do in regards to creating a budget for the utility, how much exactly fees will be, what kind of fee structure will be used and if a credit program will be included, said Kaster.

The utility budget will need to encompass operations, maintenance, infrastructure improvements, new projects, staffing, billing, legal, and regulatory compliance and public outreach. Typical stormwater utility fees range from $6 to $14 per month for a single-family residence and are included as a line item in the utility bill property owners already receive, Kasten said.

The utility would be regulated by the city council and any fee changes would be up to it as part of the budgeting process. From a public input standpoint, VanLieshout said it would be similar to other community utilities.

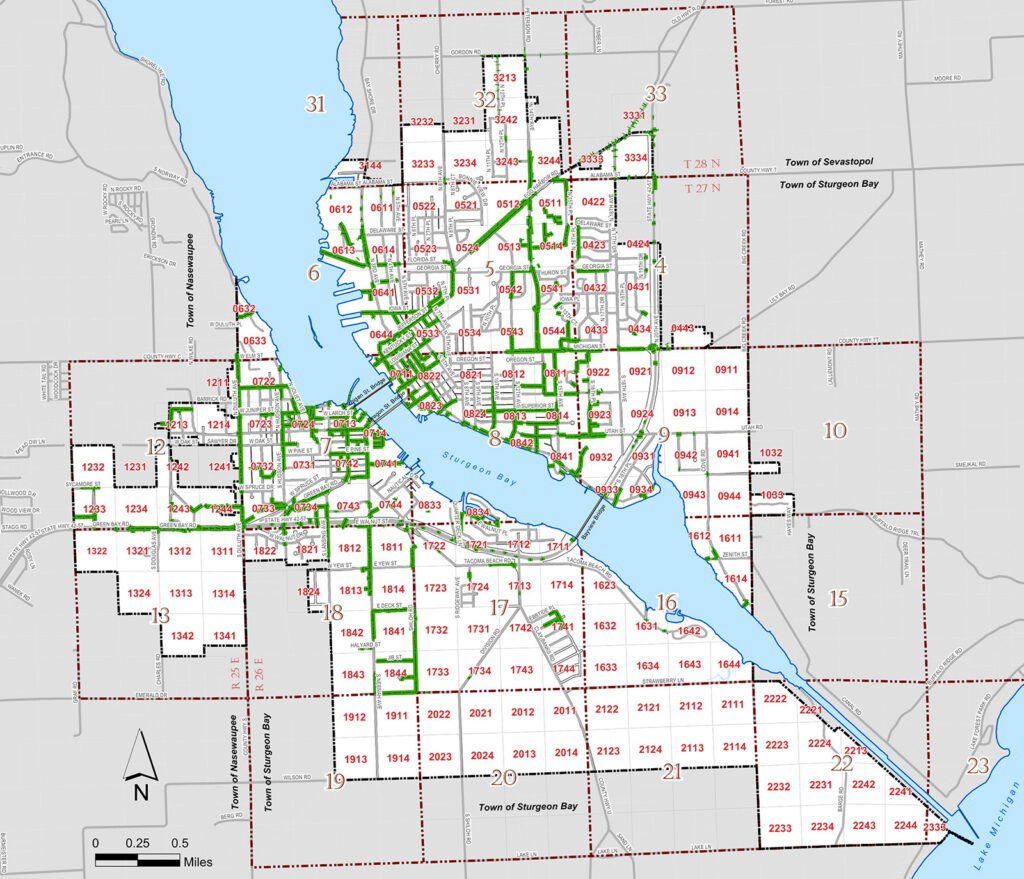

Stormwater utility fees will be calculated using an Equivalent Residential Unit or ERU, a standard unit of measurement when it comes to stormwater charge distribution. An ERU reflects the amount of impervious surface area found on a typical single-family residential property in Sturgeon Bay. Property owners will be assessed a fee based on the number of ERUs they generate.

There are several options for fee structure, including a flat rate for all residential properties or tier structures and custom rates. The city also must decide whether to incorporate residential and commercial property credits into the utility. Credits offer reduction for on-site and designed stormwater management efforts.

For a household, this can be in the form of installing rain gardens, using permeable pavers, composting and using rain barrels. For commercial and industrial properties, credits could be earned by more extensive investment in runoff mitigation like green roofs and infiltration basins that act as holding areas for stormwater to filter through soil.

The key to determining the details of the utility is balance, VanLieshout said. More fee tiers or custom fees mean more fairness, and a robust credit system means more sustainable stormwater practices and innovation. But it also means more complexity within the utility, more administration and more costs.

Public comment during the information session included several questions that presenters said would be answered further along in the process. One question was how nonprofit entities that have a lot of impervious surface and generate more ERUs, like Door County Medical Center, churches and schools, would be impacted by utility fees.

Another resident questioned what the impact to workforce housing development might be. High density properties would generate more ERUs and incur higher utility fees overall, Kaster said, and those costs could be reflected in rents or other fees.

Another question raised was where all the stormwater is going now. An analysis of the city’s current stormwater management practices and infrastructure will answer that question, Kaster said. The analysis is an MS4 permit requirement.

These decisions will be made as part of the timeline for utility creation, outlined at the April 22 information session. The necessary steps include reviewing existing infrastructure, budgeting, determining land use impacts, distribution of fees, and identifying a credit program.

City officials and Cedar Corp are soliciting public input at this point in the process, according to VanLieshout and Kaster. More information and an online form for submitting questions and feedback can be found at the city’s stormwater utility webpage.

The city will be conducting more public outreach into June and July, while working on rate and policy development. A public hearing and city council review of any proposed ordinances is anticipated in August, followed by adoption and implementation this fall. The utility itself would not be up and running until 2026 with this timeline, VanLieshout said.

Environmental stewardship perspective

Crossroads at Big Creek, a nature preserve and learning center in Sturgeon Bay, has a network of stormwater retention ponds that “probably exceed any sort of standard required,” according to Executive Director Samantha Koyen.

Crossroads’ impervious surface area consists of a quarter acre parking lot, Koyen said. The organization, which promotes environmental stewardship and education, has retention ponds on the east side of the property that snake around the back of the building, she said. There are also a handful of small artificial creek corridors that lead to Highway 42.

The system was designed for runoff management, and “we use them as part of our education practices,” Koyen explained. “Wetland exploration, frogs, dragonfly larvae. They are part of our learning tools and very different than stormwater mitigation ponds…with riprap and industrial design.”

A stormwater utility’s potential for promoting local environmental stewardship is exciting, she said, as there are a number of conflating factors in Door County that make natural resource management here unique. Shallow bedrock and not enough land mass or large enough inland water bodies to absorb excess water makes for “flashy” waterways, she said, meaning flooding can be more common or sudden than other places.

Crossroads is not acting in any official advisory capacity for the city’s stormwater utility project, Koyen said, but it does offer education and resources for anyone who wants to learn more about environmentally sustainable stormwater management practices like rain gardens and composting.